A mouse with malfunctioning buttons can be a frustrating to deal with — and usually a short leap to percussive maintenance. Standard fixes may not always last due to inferior build quality of the components, or when the microswitch won’t close at all. But, for mice that double/triple-click, will release when dragging, or mis-click on release, this Arduino-based hack may be the good medicine you’re after.

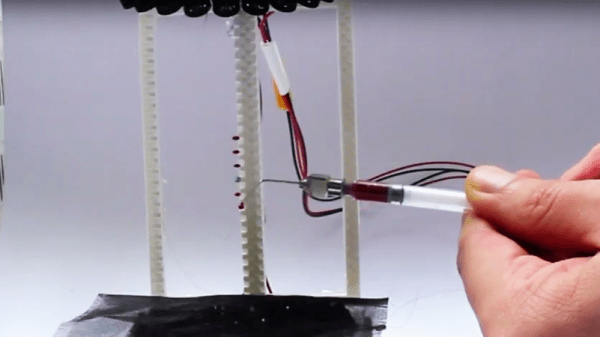

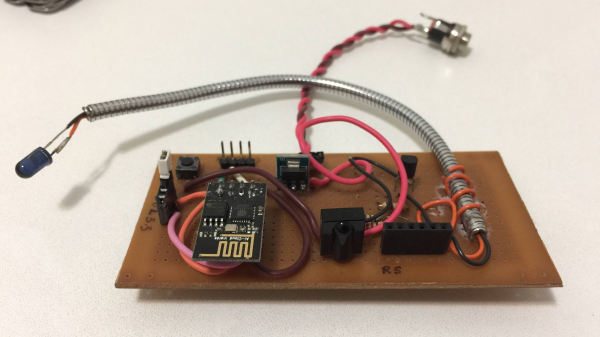

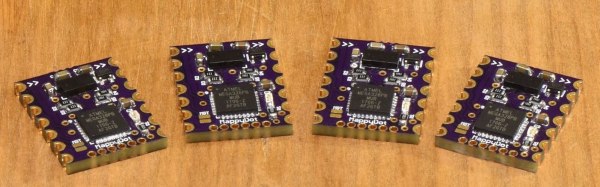

Instructables user [themoreyouknow]’s method cancels click malfunctions by latching the mouse’s controller switch trace to ‘on’ when pressed, keeping it there until the button normally closed contact closes again completely. Due to the confined spaces, you’ll want to use the smallest Arduino you can find, some insulating tape to prevent any shorts, and care to prevent damaging the wires this process adds to the mouse when you cram it all back together.

Before you take [themoreyouknow]’s guide as dogma, the are a few caveats to this hack; they are quick to point out that this won’t work on mice that share two pins between three buttons — without doing it the extra hard way, and that this might be trickier on gaming or other high-end mice, so attempt at your own peril.

Speaking of gaming mice, we recently featured a way to add some extra functionality to your mouse — cheating optional — as well as how to stash a PC inside an old Logitech model.