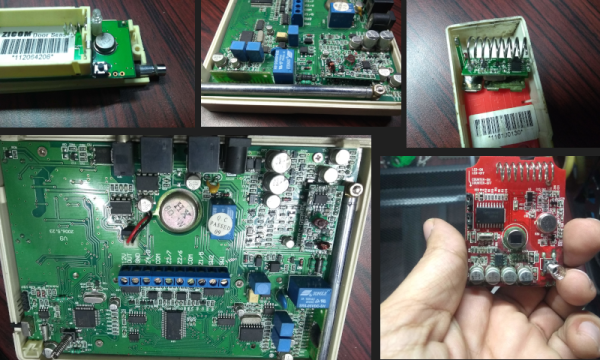

It’s hard to imagine a smart house without smart lighting. Maybe it’s laziness, but the ability to turn a light on or off without walking over to the switch is a must-have, particularly once the lap is occupied by a sleeping infant. It’s tempting to just stuff a relay in the electrical boxes and control them with a Raspberry Pi or micro-controller GPIO. While tempting, get it wrong and you have a real fire hazard. A better option is one of the integrated WiFi switches. Sonoff is probably the most well known brand, producing a whole line of devices based on the ESP8266. These devices are powered from mains power and connect to your network via WiFi. One disadvantage of Sonoff devices is they only work when connected to Sonoff’s cloud.

Light switches locked in to a cloud provider are simply not acceptable. Enter Tasmota, which we’ve covered before. Tasmota is an open source firmware, designed specifically for Sonoff switches, but supporting a wide range of ESP8266 based devices. Tasmota doesn’t connect to any cloud providers unless you tell it to, and can be completely controlled from within a local network.

Certifications, Liability, and More

We’re well acquainted with some of the pitfalls of imported electronics, but one of the lesser known problems is the lack of certification. In the United States, there are several nationally recognized testing laboratories: Underwriters Laboratories (UL) and Intertek (ETL) are the most prominent. Many imported electronic devices, including Sonoff devices, do not have either of these certifications. The problem with this is liability, should the worst ever happen and an electrical fire break out. The Internet abounds with various opinions on the importance of the certification — a missing certification mark is somewhere between meaningless and a total hazard. The most common claim is that a house fire combined with non-certified equipment installed would result in an insurance company refusing to pay.

Rather than just repeat this surely sage advice from the Internet, I asked my insurance agent about uncertified equipment in the case of a fire. I discovered that insurance agencies avoid giving definite answers about claim payments. The response that came back was “it depends”: homeowner’s insurance covers events that are accidental and sudden. If a homeowner was aware that they were using uncertified equipment, then it could be categorized as “not an accident”. So far, the myth seems plausible. The final answer from the insurance agency: it’s possible that a non UL-certified device could result in denial of payment on a claim, but it depends on the policy and other details– why take the risk? Certification marks make insurance companies happier.

I also talked to my city’s electrical inspector about the issue. He commented that non-certified equipment is a violation of electrical code when it is hard-wired into a house. He echoed the warning that an insurance company could refuse to pay, but added that in the case of injury, there could be even further liability issues. I’ve opted to use certified equipment in my house. You’ll have to make your own decision about what equipment you’re willing to use.

There are some devices on Amazon that claim to have certification, but searching the certification database leads me to believe that not all of those claims are valid. If in doubt, there is a searchable UL database, as well as a searchable Intertek database.

Continue reading “Hack My House: UL Certification And Turning The Lights On With An ESP8266” →

To solve these problems, [theguymasamato] decided to design his own stackable boxes to store small and light objects far more efficiently than before. The design also allows the boxes to be made in a variety of sizes without changing any of the 3D printed parts. Carefully measured and cut cardboard is critical, but that’s nothing a utility knife and ruler can’t solve. The only other requirements are a few simple plastic parts, and some glue. He can fit six of these inside a single one of his drawers with enough room to access and handle them, but without wasting space.

To solve these problems, [theguymasamato] decided to design his own stackable boxes to store small and light objects far more efficiently than before. The design also allows the boxes to be made in a variety of sizes without changing any of the 3D printed parts. Carefully measured and cut cardboard is critical, but that’s nothing a utility knife and ruler can’t solve. The only other requirements are a few simple plastic parts, and some glue. He can fit six of these inside a single one of his drawers with enough room to access and handle them, but without wasting space.