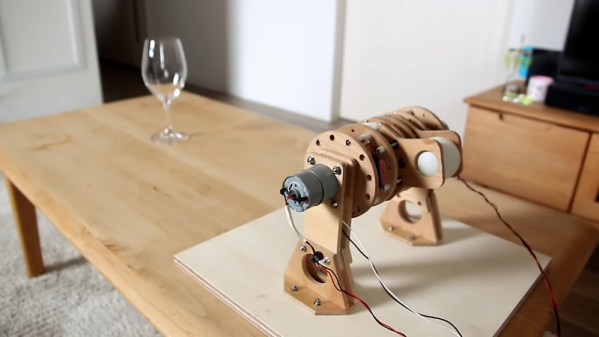

We hackers just can’t get enough of sorters for confections like Skittles and M&Ms, the latter clearly being the superior candy in terms of both sorting and snackability. Sorting isn’t just about taking a hopper of every color and making neat monochromatic piles, though. [JohnO3] noticed that all those colorful candies would make dandy pixel art, so he built a bot to build up images a Skittle at a time.

Dubbed the “Pixel8R” after the eight colors in a regulation bag of Skittles, the machine is a largish affair with hoppers for each color up top and a “canvas” below with Skittle-sized channels and a clear acrylic cover. The hoppers each have a rotating disc with a hole to meter a single Skittle at a time into a funnel which is connected to a tube that moves along the top of the canvas one column at a time. [JohnO3] has developed a software toolchain to go from image files to Skittles using GIMP and a Python script, and the image builds up a row at a time until 2,760 Skittle-pixels have been placed.

Dubbed the “Pixel8R” after the eight colors in a regulation bag of Skittles, the machine is a largish affair with hoppers for each color up top and a “canvas” below with Skittle-sized channels and a clear acrylic cover. The hoppers each have a rotating disc with a hole to meter a single Skittle at a time into a funnel which is connected to a tube that moves along the top of the canvas one column at a time. [JohnO3] has developed a software toolchain to go from image files to Skittles using GIMP and a Python script, and the image builds up a row at a time until 2,760 Skittle-pixels have been placed.

The downside: sorting the Skittles into the hoppers. [JohnO3] does this manually now, but we’d love to see a sorter like this one sitting up above the hoppers. Or, he could switch to M&Ms and order single color bags. But where’s the fun in that?

[via r/arduino]