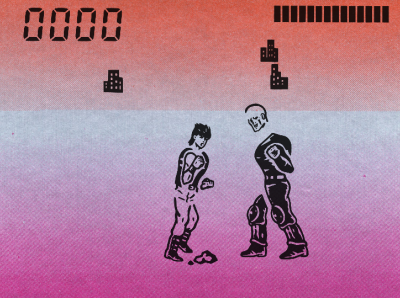

There’s a certain class of hardware only millennials will cherish. Those cheap ‘LCD Video Games’ from Tiger Electronics were sold in the toy aisle of your old department store. There was an MC Hammer video game. There was a Stargate video game. There was a Back To The Future video game. All of these used the same plastic enclosure, all of them had Up, Down, Left, Right, and two extra buttons, and all of them used a custom liquid crystal display. All of them were just slightly disappointing.

Now, there’s an effort to digitize and preserve these video games on archive.org, along with every other variety of ancient handheld and battery powered video game from ages past.

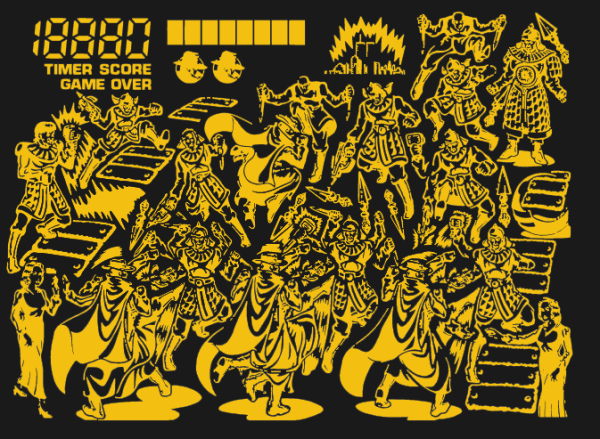

This is an effort from volunteers of the MAME team, who are now in the process of bringing these ‘LCD Video Games’ to the Internet Archive. Unlike other games which are just bits and bytes along with a few other relatively easily-digitized manuals and Peril Sensitive Sunglasses, preserving these games requires a complete teardown of the device. These are custom LCDs, after all. [Sean Riddle] and [hap] have been busy tearing apart these LCDs, vectorizing the segments (the game The Shadow is seen above), and preserving the art behind the LCD. It’s an immense amount of work, but the process has been refined somewhat over the years.

Some of these games, and some other earlier games featuring VFD and LED displays, are now hosted on the Internet Archive for anyone to play in a browser. The Handheld History collection joins the rest of the emulated games on the archive, with the hope they’ll be preserved for years to come.