This article is about crypto. It’s in the title, and the first sentence, yet the topic still remains hidden.

At Hackaday, we are deeply concerned with language. Part of this is the fact that we are a purely text-based publication, yes, but a better reason is right there in the masthead. This is Hackaday, and for more than a decade, we have countered to the notion that ‘hackers’ are only bad actors. We have railed against co-opted language for our entire existence, and our more successful stories are entirely about the use and abuse of language.

Part of this is due to the nature of the Internet. Pedantry is an acceptable substitute for wisdom, it seems, and choosing the right word isn’t just a matter of semantics — it’s a compiler error. The wrong word shuts down all discussion. Use the phrase, ‘fused deposition modeling’ when describing a filament-based 3D printer, and some will inevitably reach for their pitchforks and torches; the correct phrase is, ‘fused filament fabrication’, the term preferred by the RepRap community because it is legally unencumbered by patents. That’s actually a neat tidbit, but the phrase describing a technology is covered by a trademark, and not by a patent.

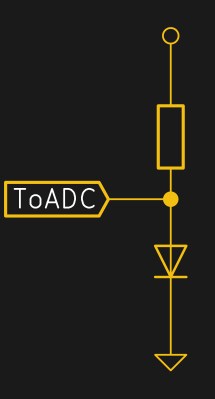

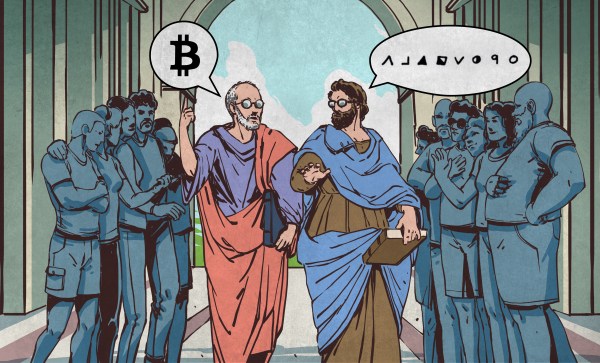

The technical side of the Internet, or at least the subpopulation concerned about backdoors, 0-days, and commitments to hodl, is now at a semantic crossroads. ‘Crypto’ is starting to mean ‘cryptocurrency’. The netsec and technology-minded populations of the Internet are now deeply concerned over language. Cryptocurrency enthusiasts have usurped the word ‘crypto’, and the folks that were hacking around with DES thirty years ago aren’t happy. A DH key exchange has nothing to do with virtual cats bought with Etherium, and there’s no way anyone losing money to ICO scams could come up with an encryption protocol as elegant as ROT-13.

But language changes. Now, cryptographers are dealing with the same problem hackers had in the 90s, and this time there’s nothing as cool as rollerblading into the Gibson to fall back on. Does ‘crypto’ mean ‘cryptography’, or does ‘crypto’ mean cryptocurrency? If frequency of usage determines the correct definition, a quick perusal of the press releases in my email quickly reveals a winner. It’s cryptocurrency by a mile. However, cryptography has been around much, much longer than cryptocurrency. What’s the right definition of ‘crypto’? Does it mean cryptography, or does it mean cryptocurrency?

![You can tell [Dr. Seuss] is thinking about his next volume: <em>How The Grinch Stole Whoville Hackspace</em>. Al Ravenna, World Telegram [Public domain].](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/1003px-ted_geisel_nywts.jpg?w=392)