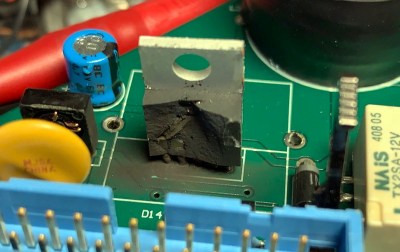

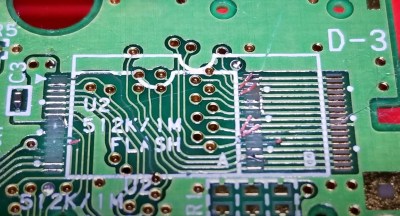

The flash chips used in Game Boy Advance (GBA) cartridges were intended to be more reliable and less bulky than the battery-backed SRAM used to save player progress on earlier systems. But with some GBA titles now hitting their 20th anniversary, it’s not unheard of for older carts to have trouble loading saves or creating new ones. Perhaps that’s why the previous owner tried to reflow the flash chip on their copy of Golden Sun, but as [Taylor Burley] found after he opened up the case, they only ended up making the situation worse.

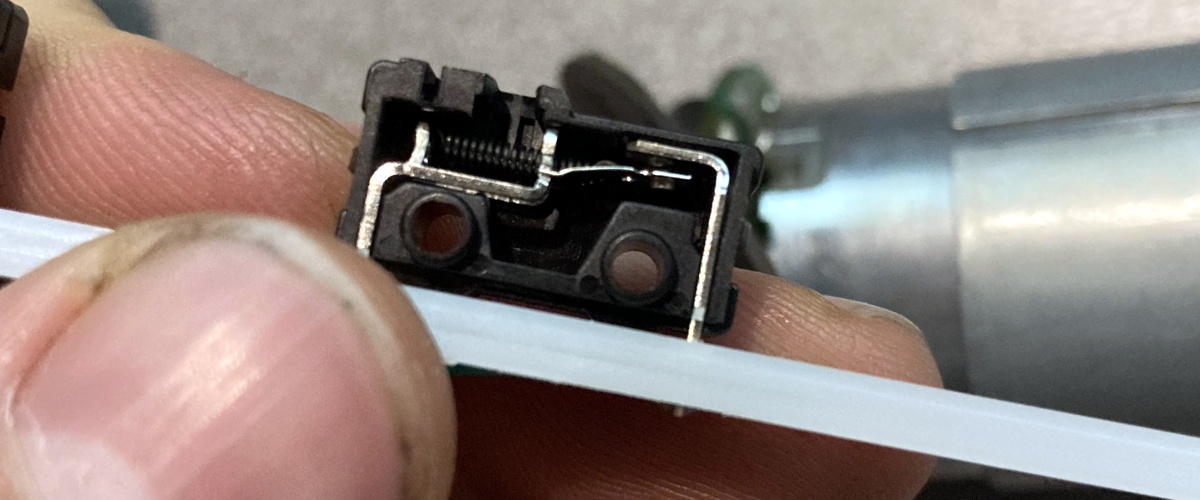

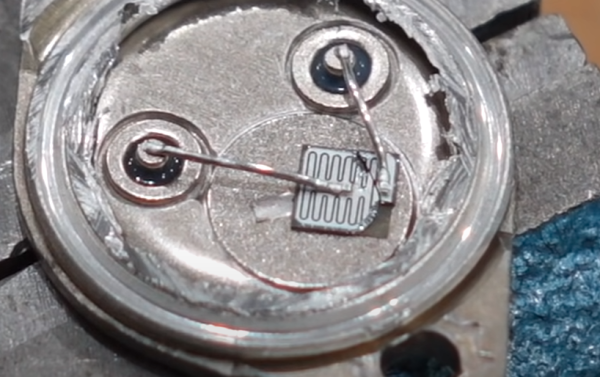

When presented with so many damaged traces on the PCB, the most reasonable course of action would have been to get a donor cartridge and swap the save chips. But a quick check on eBay shows that copies of Golden Sun don’t exactly come cheap. So [Taylor] decided to flex his soldering muscles and repair each trace with a carefully bent piece of 30 gauge wire. If you need your daily dose of Zen, just watch his methodical process in the video below.

While it certainly doesn’t detract from [Taylor]’s impressive soldering work, it should be said that the design of the cartridge PCB did help out a bit, as many of the damaged traces had nearby vias which gave him convenient spots to attach his new wires. It also appears the PCB was designed to accept flash chips of varying physical dimensions, which provided some extra breathing room for the repairs.

Seeing his handiwork, it probably won’t surprise you to find that this isn’t the first time [Taylor] has performed some life-saving microsurgery. Just last year he was able to repair the PCB of an XBox controller than had literally been snapped in half.

Continue reading “Steady Hand Brings GBA Cart Back From The Grave”