When the Magic Smoke is released, chances are pretty good that you’ve got some component-level diagnosis to do. It’s usually not that hard to find the faulty part, charred and crusty as it likely appears. In that case, some snips, a new non-crusty part, and a little solder are usually enough to get you back in business.

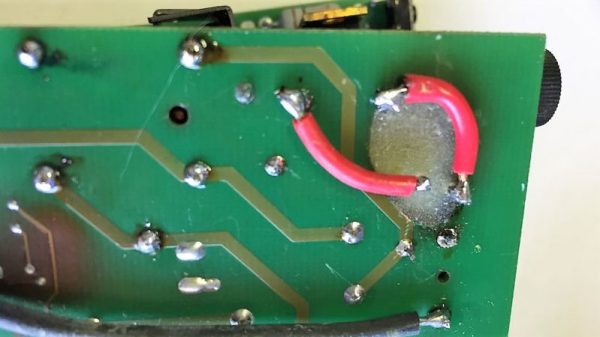

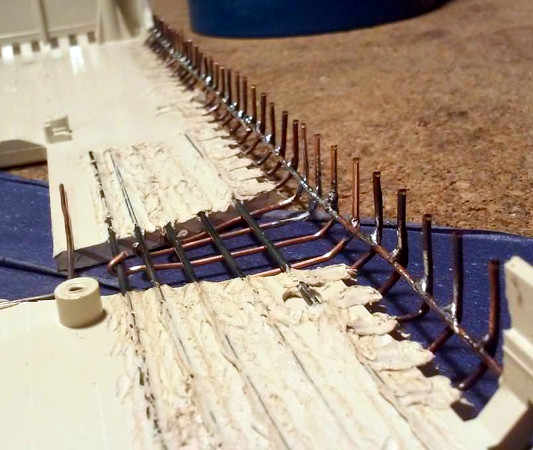

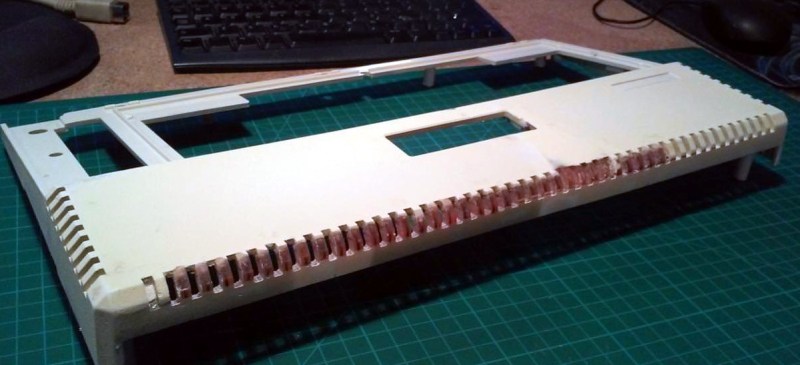

But what if the smoke came not from a component but from the PCB itself? [Happymacer] chanced upon this sorry situation in a power supply for an electric gate opener. Basking in the Australian sunshine for a few years, the opener started acting fussy at first, then not acting at all. Inspection of its innards revealed that some unlucky ants had shorted across line and neutral on the power supply board, which burned not only the traces but the FR4 of the board as well. Rather than replace the entire board, [Happymacer] carefully removed the carbonized (and therefore conductive) fiberglass and resin, leaving a gaping hole in the board. He fastened a patch for the hole from some epoxy glue; Araldite is the brand he used, but any two-part epoxy, like JB Weld, should work. One side of the hole was covered with tape and the epoxy was smeared into the hole, and after a week of curing and a little cleanup, it was ready for duty. The components were placed into freshly drilled holes, missing traces were replaced with wire, and it seems to be working fine.

This seems like a great tip to keep in mind for when catastrophe strikes your boards. There are more extreme ways to do it, of course, but perhaps none so flexible. After all, epoxy is versatile stuff.