After spending much of the 20th century languishing in development hell, electric cars have finally hit the roads in a big way. Automakers are working feverishly to improve range and recharge times to make vehicles more palatable to consumers.

With a strong base of sales and increased uncertainty about the future of fossil fuels, improvements are happening at a rapid pace. Oftentimes, change is gradual, but every so often, a brand new technology promises to bring a step change in performance. Silicon carbide (SiC) semiconductors are just such a technology, and have already begun to revolutionise the industry.

Mind The Bandgap

Traditionally, electric vehicles have relied on silicon power transistors in their construction. Having long been the most popular semiconductor material, new technological advances have opened it up to competition. Different semiconductor materials have varying properties that make them better suited for various applications, with silicon carbide being particularly attractive for high-power applications. It all comes down to the bandgap.

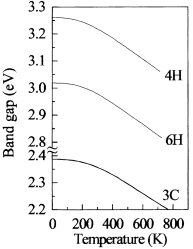

Electrons in a semiconductor can sit in one of two energy bands – the valence band, or the conducting band. To jump from the valence band to the conducting band, the electron needs to reach the energy level of the conducting band, jumping the band gap where no electrons can exist. In silicon, the bandgap is around 1-1.5 electron volts (eV), while in silicon carbide, the band gap of the material is on the order of 2.3-3.3 eV. This higher band gap makes the breakdown voltage of silicon carbide parts far higher, as a far stronger electric field is required to overcome the gap. Many contemporary electric cars operate with 400 V batteries, with Porsche equipping their Taycan with an 800 V system. The naturally high breakdown voltage of silicon carbide makes it highly suited to work in these applications.

Continue reading “New Silicon Carbide Semiconductors Bring EV Efficiency Gains”

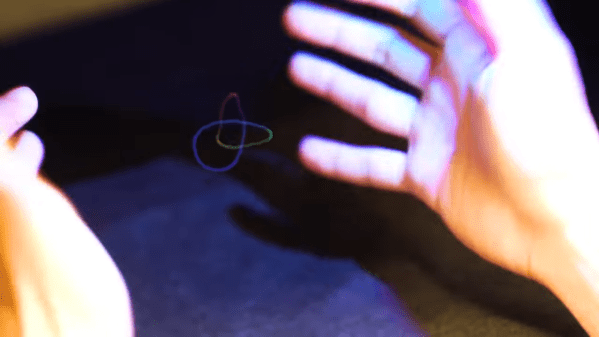

We’ve seen 3D image projection tried in a variety of different ways, but this is a new one to us. This volumetric display by Interact Lab of the University of Sussex

We’ve seen 3D image projection tried in a variety of different ways, but this is a new one to us. This volumetric display by Interact Lab of the University of Sussex