Today we take the concept of a centralized software repository for granted. Whether it’s apt or the App Store, pretty much every device we use today has a way to pull applications in without the user manually having to search for them on the wilds of the Internet. Not only is this more convenient for the end user, but at least in theory, more secure since you won’t be pulling binaries off of some random website.

But centralized software distribution doesn’t just benefit the user, it can help developers as well. As platforms like Steam have shown, once you lower the bar to the point that all you need to get your software on the marketplace is a good idea, smaller developers get a chance to shine. You don’t need to find a publisher or pay out of pocket to have a bunch of discs pressed, just put your game or program out there and see what happens. Markus “Notch” Persson saw his hobby project Minecraft turn into one of the biggest entertainment franchises in decades, but one has to wonder if it would have ever gotten released commercially if he first had to convince a publisher that somebody would want to play a game about digging holes.

But centralized software distribution doesn’t just benefit the user, it can help developers as well. As platforms like Steam have shown, once you lower the bar to the point that all you need to get your software on the marketplace is a good idea, smaller developers get a chance to shine. You don’t need to find a publisher or pay out of pocket to have a bunch of discs pressed, just put your game or program out there and see what happens. Markus “Notch” Persson saw his hobby project Minecraft turn into one of the biggest entertainment franchises in decades, but one has to wonder if it would have ever gotten released commercially if he first had to convince a publisher that somebody would want to play a game about digging holes.

In the days before digital distribution was practical, things were even worse. If you wanted to sell your game or program, it needed to be advertised somewhere, needed to be put on physical media, and it needed to get shipped out to the customer. All this took capital that would easily be beyond many independent developers, to say nothing of single individuals.

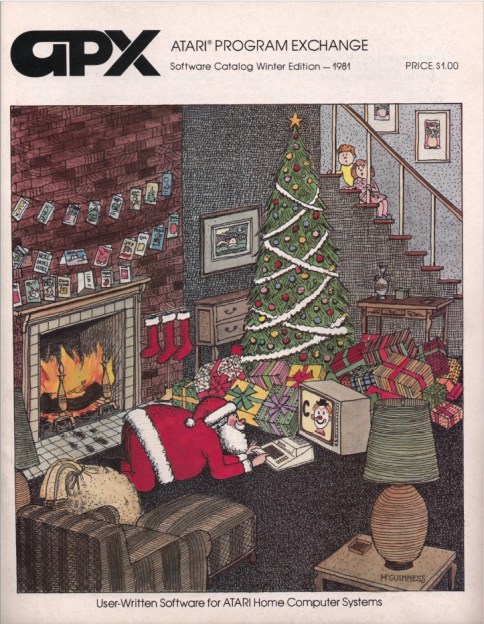

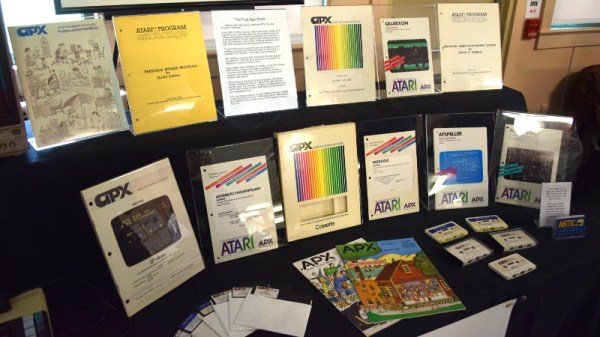

But at the recent Vintage Computer Festival East, [Allan Bushman] showed off relics from a little known chapter of early home computing: the Atari Program Exchange (APX). In a wholly unique approach to software distribution at the time, individuals were given a platform by which their software would be advertised and sold to owners of 8-bit machines such as the Atari 400/800 and later XL series computers. In the early days, when the line between computer user and computer programmer was especially blurry, the APX let anyone with the skill turn their ideas into profit. Continue reading “VCF East 2018: The Mail Order App Store”

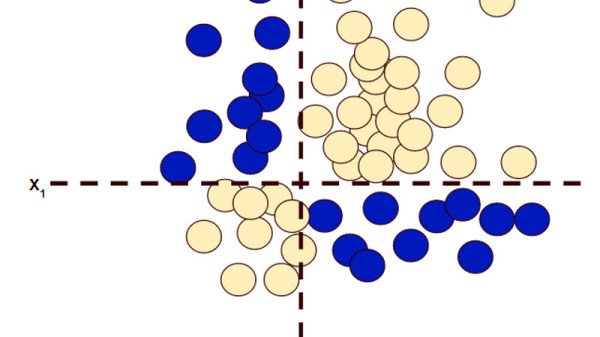

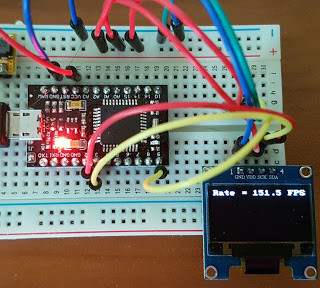

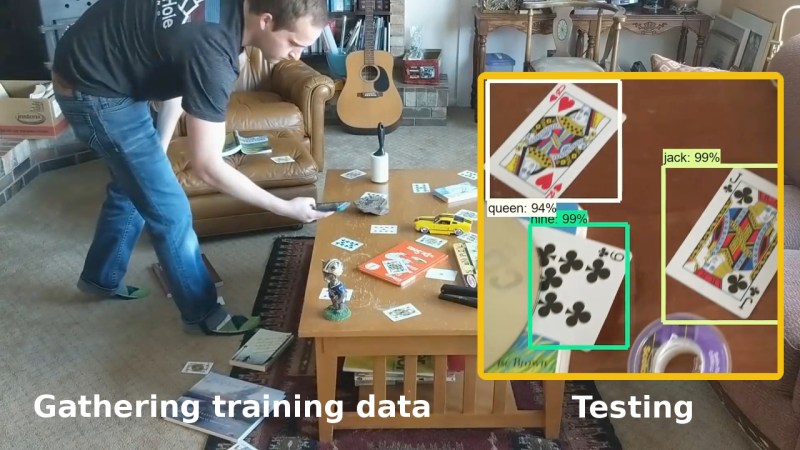

You’ll need a few hundred images of your objects. These can either be scraped from an online source like Google’s images or you get take your own photos. If you use the latter approach, make sure to shoot from various angles, rotations, and with different lighting conditions. Fill your background with various other things and even have some things partially obscuring your objects. This may sound like a long, tedious task, but it can be done efficiently. [Edje Electronics] is working on recognizing playing cards so he first sprinkled them around his living room, added some clutter, and walked around, taking pictures using his phone. Once uploaded, some easy-to-use software helped him to label them all in around an hour. Note that he trained on 24 different objects, which are the number of different cards you get in a

You’ll need a few hundred images of your objects. These can either be scraped from an online source like Google’s images or you get take your own photos. If you use the latter approach, make sure to shoot from various angles, rotations, and with different lighting conditions. Fill your background with various other things and even have some things partially obscuring your objects. This may sound like a long, tedious task, but it can be done efficiently. [Edje Electronics] is working on recognizing playing cards so he first sprinkled them around his living room, added some clutter, and walked around, taking pictures using his phone. Once uploaded, some easy-to-use software helped him to label them all in around an hour. Note that he trained on 24 different objects, which are the number of different cards you get in a