It’s a fair bet that anyone regularly reading Hackaday has a voltmeter within arm’s reach, and there’s a good chance an oscilloscope isn’t far behind. But beyond that, things get a little murky. We’re sure some of you have access to a proper lab full of high-end test gear, even if only during business hours, but most of us have to make do with the essentials due to cost and space constraints.

The ideal solution is a magical little box that could be whatever piece of instrumentation you needed at the time: some days it’s an oscilloscope, while others it’s a spectrum analyzer, or perhaps even a generic data logger. To simplify things the device wouldn’t have a physical display or controls of its own, instead, you could plug it into your computer and control it through software. This would not only make the unit smaller and cheaper, but allow for custom user interfaces to be created that precisely match what the user is trying to accomplish.

Wishful thinking? Not quite. As guest host Ben Nizette explained during the Software Defined Instrumentation Hack Chat, the dream of replacing a rack of test equipment with a cheap pocket-sized unit is much closer to reality than you may realize. While software defined instruments might not be suitable for all applications, the argument could be made that any capability the average student or hobbyist is likely to need or desire could be met by hardware that’s already on the market.

Wishful thinking? Not quite. As guest host Ben Nizette explained during the Software Defined Instrumentation Hack Chat, the dream of replacing a rack of test equipment with a cheap pocket-sized unit is much closer to reality than you may realize. While software defined instruments might not be suitable for all applications, the argument could be made that any capability the average student or hobbyist is likely to need or desire could be met by hardware that’s already on the market.

Ben is the Product Manager at Liquid Instruments, the company that produces the Moku line of multi-instruments. Specifically, he’s responsible for the Moku:Go, an entry-level device that’s specifically geared for the education and maker markets. The slim device doesn’t cost much more than a basic digital oscilloscope, but thanks to the magic of software defined instrumentation (SDi), it can stand in for eleven instruments — all more than performant enough for their target users.

So what’s the catch? As you might expect, that’s the first thing folks in the Chat wanted to know. According to Ben, the biggest drawback is that all of your instrumentation has to share the same analog front-end. To remain affordable, that means everything the unit can do is bound by the same fundamental “Speed Limit” — which on the Moku:Go is 30 MHz. Even on the company’s higher-end professional models, the maximum bandwidth is measured in hundreds of megahertz.

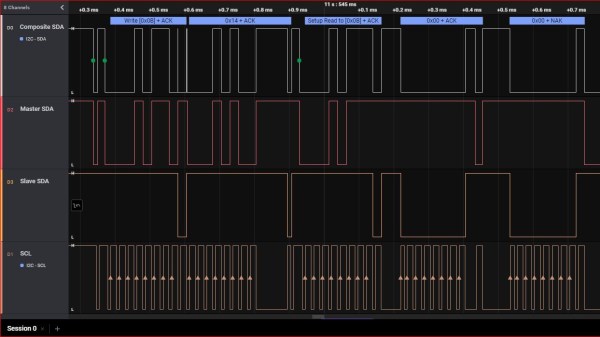

Additionally, SDI has traditionally been limited to the speed of the computer it was attached to. But the Moku hardware manages to sidestep this particular gotcha by running the software side of things on an internal FPGA. The downside is that some of the device’s functions, such as the data logger, can’t actually live stream the data to the connected computer. Users will have to wait until the measurements are complete before they pull the results off, though Ben says there’s enough internal memory to store months worth of high-resolution data.

Of course, as soon as this community hears there’s an FPGA on board, they want to know if they can get their hands on it. To that end, Ben says the Moku:Go will be supported by their “Cloud Compile” service in June. Already available for the Moku:Pro, the browser-based application allows you to upload your HDL to the Liquid Instruments servers so it can be built and optimized. This gives power users complete access to the Moku hardware so they can build and deploy their own custom features and tools that precisely match their needs without a separate development kit. Understanding that obsolescence is always a problem with a cloud solution, Ben says they’re also working with Xilinx to allow users to do builds on their own computers while still implementing the proprietary “secret sauce” that makes it a Moku.

It’s hard not to get excited about the promise of software defined instrumentation, especially with companies like Liquid Instruments and Red Pitaya bringing the cost of the hardware down to the point where students and hackers can afford it. We’d like to thank Ben Nizette for taking the time to talk with the community about what he’s been working on, especially given the considerable time difference between the Hackaday Command Center and Liquid’s Australian headquarters. Anyone who’s willing to jump online and chat about FPGAs and phasemeters before the sun comes up is AOK in our book.

The Hack Chat is a weekly online chat session hosted by leading experts from all corners of the hardware hacking universe. It’s a great way for hackers connect in a fun and informal way, but if you can’t make it live, these overview posts as well as the transcripts posted to Hackaday.io make sure you don’t miss out.