Do you like the sleek look of Apple’s laptops? Are you a fan of the Raspberry Pi? Have a particular affinity for hot glue and 3D printed plastic? Then you’re in luck, because this tiny “MacBook” built by serial miniaturizer [Michael Pick] features all of the above (and a good bit more) in one palm-sized package. (Video link, embedded below.)

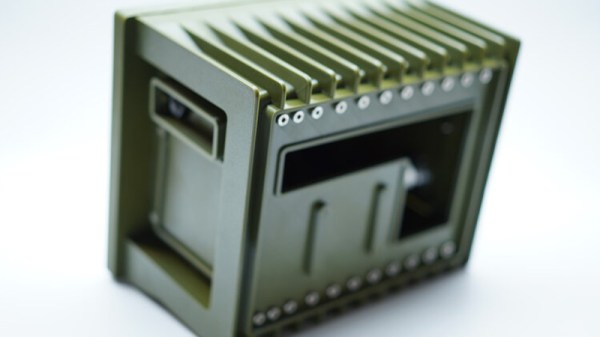

Getting the LCD panel and Raspberry Pi 4 to fit into the slim 3D printed case took considerable coaxing. In the video after the break, you can see [Michael] strip off any unnecessary components that would stand in his way. The LCD panel had to lose its speakers and buttons, and the Pi has had its Ethernet and USB ports removed. While space was limited, he did manage to squeeze an illuminated resin-printed Apple logo into the lid of the laptop to help sell the overall look.

The bottom half of the machine has a number of really nice details, like the fan grill cut from metal hardware cloth and a functional “MagSafe” connector made from a magnetic USB cable. The keyboard PCB and membrane was liberated from a commercially available unit, all [Michael] needed to do was model in the openings for the keys. Since the keyboard already came with its own little trackpad, the lower one is just there for looks.

The bottom half of the machine has a number of really nice details, like the fan grill cut from metal hardware cloth and a functional “MagSafe” connector made from a magnetic USB cable. The keyboard PCB and membrane was liberated from a commercially available unit, all [Michael] needed to do was model in the openings for the keys. Since the keyboard already came with its own little trackpad, the lower one is just there for looks.

Speaking of which, to really drive home the Apple aesthetic, [Michael] made the bold move of covering up all the screws with body filler after assembly. It’s not a technique we’d necessarily recommend, but gluing it shut would probably have made it even harder to get back into down the line.

We’ve previously seen [Michael] create a miniature rendition of the iMac and an RGB LED equipped “gaming” computer using many of the same parts and techniques. He’ll have to start branching off into less common machines to replicate soon, which reminds us that we’re about due for another tiny Cray X-MP.

Continue reading “3D Printed Mini MacBook With A Raspberry Pi Heart”