One day, [Samy]’s best friend [Matt] mentioned he had a wireless doorbell. Astonishing. Even more amazing is the fact that anyone can buy a software defined radio for $20, a small radio module from eBay for $4, and a GSM breakout board for $40. Connect these pieces together, and you have a device that can ring [Matt]’s doorbell from anywhere on the planet. Yes, it’s the ultimate over-engineered ding dong ditch, and a great example of how far you can take practical jokes if you know which end of a soldering iron to pick up.

Simply knowing [Matt] has a wireless doorbell is not enough; [Samy] needed to know the frequency, the modulation scheme, and what the doorbell was sending. Some of this information can be found by looking up the FCC ID, but [Samy] found a better way. When [Matt] was out of his house, [Samy] simply rang the doorbell a bunch of times while looking at the waterfall plot with an RTL-SDR TV tuner. There are a few common frequencies tiny, cheap remote controls will commonly use – 315 MHz, 433 MHz, and 900 MHz. Eventually, [Samy] found the frequency the doorbell was transmitting at – 433.8 MHz.

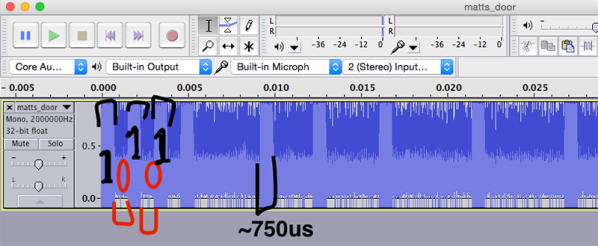

After capturing the radio signal from the doorbell, [Samy] looked at the audio waveform in Audacity. It looked like this doorbell used On-Off Keying, or just turning the radio on for a binary ‘1’ and off for a binary ‘0’. In Audacity, everything the doorbell transmits becomes crystal clear, and with a $4 434 MHz transmitter from SparkFun, [Samy] can replicate the output of the doorbell.

For the rest of the build, [Samy] is using a mini GSM cellular breakout board from Adafruit. This module listens for any text message containing the word ‘doorbell’ and sends a signal to an Arduino. The Arduino then sends out the doorbell code with the transmitter. It’s evil, and extraordinarily over-engineered.

Right now, the ding dong ditch project is set up somewhere across the street from [Matt]’s house. The device reportedly works great, and hopefully hasn’t been abused too much. Video below.

Continue reading “Over-engineering Ding Dong Ditch” →