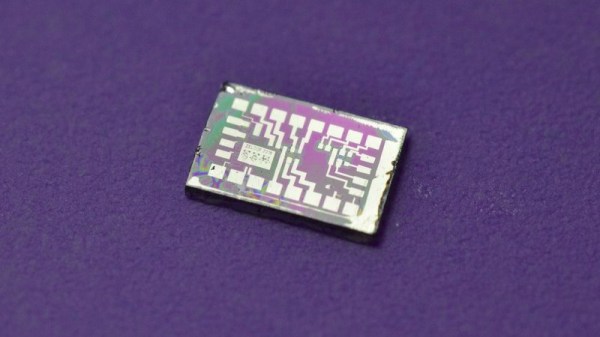

A few days ago we brought you news of [Sam Zeloof]’s amazing achievement, of creating the first home-made lithographically produced integrated circuit. It was a modest enough design in a simple pair of differential amplifiers and all we had to go on was a Twitter announcement, but it promised a more complete write-up to follow. We’re pleased to note that the write-up has arrived, and we can have a look at some of the details of just how he managed to produce an IC in his garage. He’s even given it a part number, the Zeloof Z1.

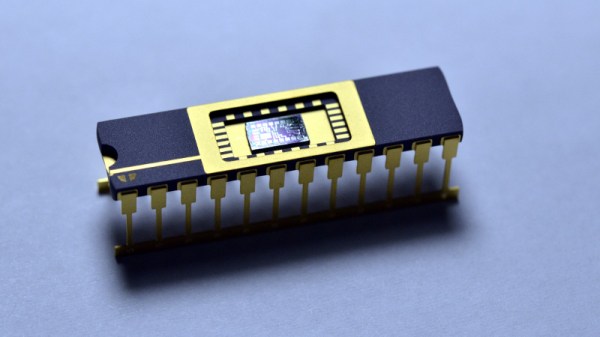

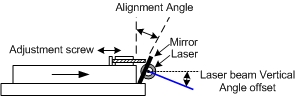

For ease of manufacture he’s opted for a PMOS process, and he is using four masks which he lists as the active/doped area, gate oxide, contact window, and top metal. He takes us through 66 different processes that he performs over the twelve hours of a full production run, with comprehensive descriptions that make for a fascinating run-down of semiconductor manufacture for those of us who will never build a chip of our own but are still interested to learn how it is done. The chip’s oblong dimensions are dictated by the constraints of an off-the-shelf Kyocera ceramic chip carrier, though without a wire bonding machine he’s unable to do any more than test it with probes.

You can read our reporting of his first announcement, but don’t go away thinking that will be all. We’re certain [Sam] will be back with more devices, and can’t wait to see the Z2.