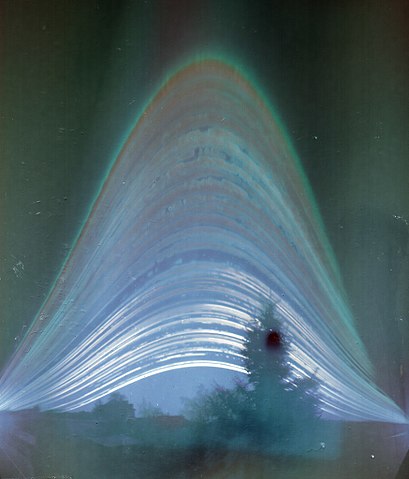

Have you ever heard of solargraphy? The name tells you much of what you need to know, but the images created with a homemade pinhole camera and a piece of photographic film can be visually arresting, showing as they do the cumulative tracks of the sun’s daily journey across the sky over many months. But what if you don’t want to use film? Is solargraphy out of reach to the digital photographers of the world?

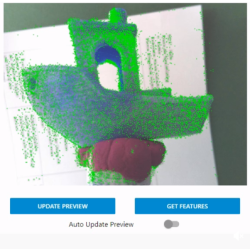

Not at all, thanks to this digital solargraphy setup. [volzo] searched for a way to make a digital camera perform like a film-based solargraphic camera, first thinking to take a series of images during the day and average them together. He found that this just averaged out the sun from the final image. His solution was to take a pair of photos at each timepoint — one correctly exposed to capture the scene, and one stopped way down to just capture the position of the sun as a pinprick of light. All the foreground images are averaged, while the stopped-down sun images are overlaid upon each other, producing the track of the sun across the sky. Add the two resulting images and you’ve got a solargraph.

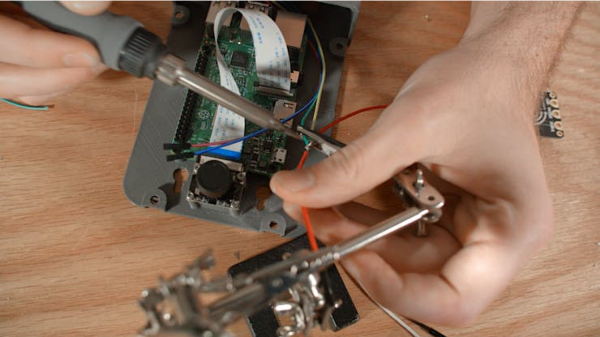

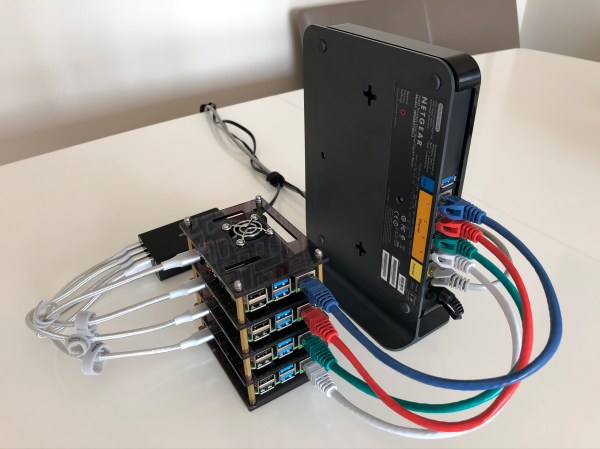

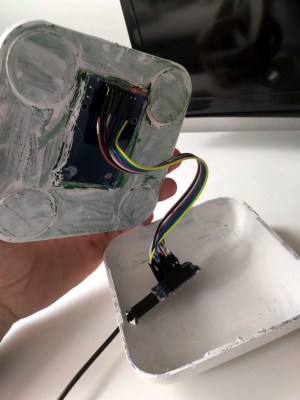

To automate the process, [volzo] used a Raspberry Pi and a Pi-Cam fitted in a weatherproof 3D-printed box. A custom hat powers up the Pi every few minutes, which boots up and takes the two pictures. Sadly, the batteries only last for a couple of days, so those long six-month exposures aren’t possible yet. But [volzo] has made all the sources available, so feel free to build on his work. If you prefer to use a DSLR for the job, this Bluetooth intervalometer might help.