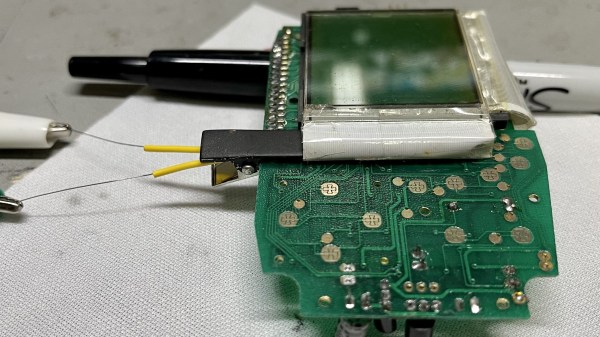

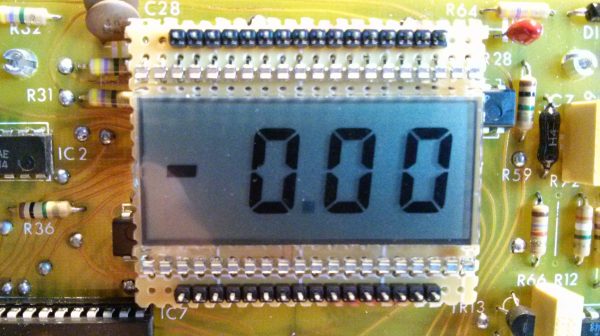

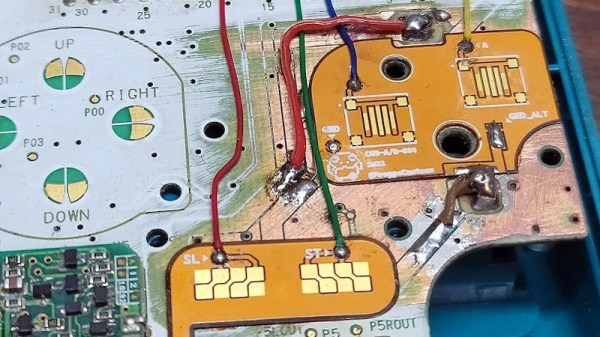

[Stephen] writes to us about an LCD repair tool he has created. We’ve all seen old devices with monochrome LCDs connected by thin film, where connections between the PCB and the LCD have deteriorated and the LCD would no longer show parts of the picture. This is a connection heating gadget, that [Stephen] affectionately dubs as World’s Smallest Hair Straightener, made specifically to bring cool old tech back to life.

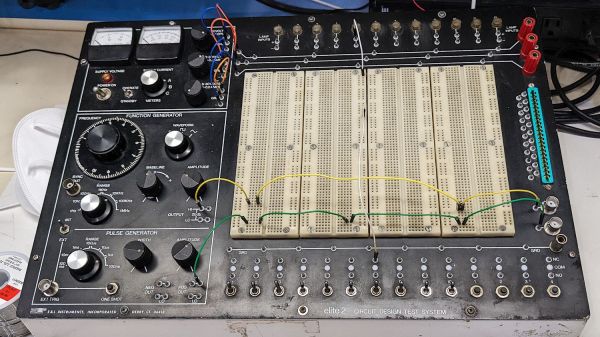

A resin-printed mold houses a coil of Kanthal wire, easy to source and simple to make. He reuses a hair clip as a housing for the heating element, which also provides pressure needed to squish the film-printed conductive traces into the LCD as the adhesive melts. High-temperature epoxy brings the two together, and with a variable power supply, this tool successfully brought an old Tiger 99x handheld back to life.

This hack was made possible, in part, because of [JohnDevin Duncan] in Hackaday comment section sharing his experience on repairing LCD ribbons back in 2015, giving valuable insights on the problem that we initially thought would be solve-able with a soldering iron. The knowledge shared was distilled by [Stephen] into a tool that we all can now use when we encounter a device we really, really want to revive.

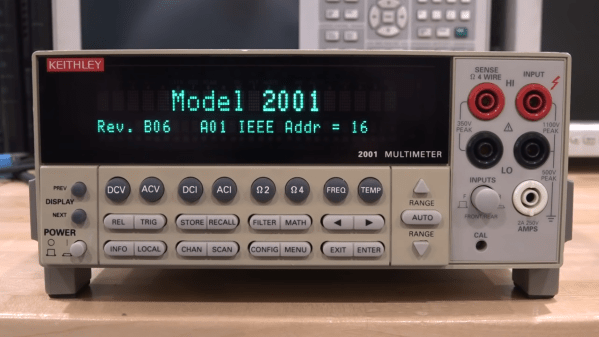

Last time we covered this topic, quite a few hackers popped up with their stories and suggestions. Old game console fix stories are a staple here on Hackaday, a few pop to mind – this high-effort trace repair of a water-damaged GameBoy cartridge, a badly designed NES cartridge socket reinvention, and this GameBoy LCD sunburn damage restoration guide.