[Bruce Land] of Cornell University will be a familiar name to many Hackaday readers, searching the site for ‘ECE4760′ will bring up many interesting topics around embedded programming. Every year [Bruce] releases yet more of the students’ work out into the wild to our great delight. This RP2040-based project is a bit more abstract than some previous work and shows yet another implementation of an older hack to utilise the DMA hardware of the RP2040 as another CPU core. While the primary focus of the RP2040 DMA subsystem is moving data between memory spaces, with minimal CPU intervention, the DMA control blocks have some fairly complex behaviour. This allows for a Turing-complete CPU to be implemented purely with the DMA hardware and a sprinkling of memory.

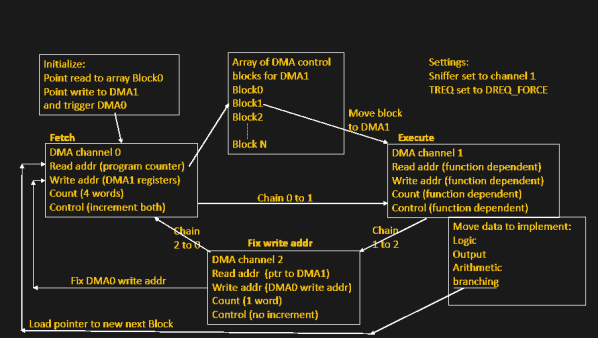

The method ties up three of the twelve DMA channels, and is estimated to have a similar performance to ‘an Arduino’ but [Bruce] doesn’t specify which one of the varied models that could be. But who cares anyway? Programming the CPU is a matter of leveraging the behaviour of the hardware, which is all memory mapped and targetable by the DMA. For example, the CPU can waggle GPIO pins by using the DMA to write values to the peripheral address space. The basic flow can be seen in the image above. DMA0 is used as the program counter, which points DMA1 to an array of DMA control blocks, a sequence of which codes for some of the ‘opcodes’ of the CPU model. DMA0 chains to (hands over control to) DMA1 which reads the control blocks and configures itself accordingly. DMA1 performs whatever data move is programmed, chains to DMA2, which in turn reprograms the DMA0 program counter to point to the next block in the list to be executed by DMA1.