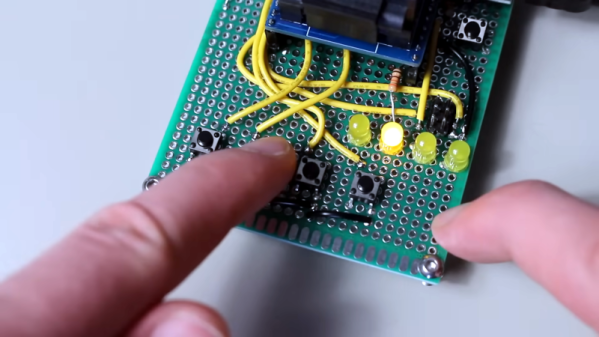

USB is a well-defined standard for which there are a reasonable array of connectors for product designers to use in whatever their application is. Which of course means that so many manufacturers have resorted to using proprietary connectors, probably to ensure that replacements are suitably overpriced. [Teaching Tech] had this problem with a fancy in-car video device, but rather than admit defeat with a missing cable, he decided to create his own replacement from scratch.

The plug in use was a multi-way round design probably chosen to match the harshness of the automotive environment. The first solution was to hook up a USB cable to a set of loose pins, but after a search to find the perfect-fitting set of pins a 3D printed housing was designed to replace the shell of the original. There’s an ouch moment in the video below the break as he receives a hot glue burn while assembling the final cable, but the result is a working and easy to use cable that allows access to all the device functions. Something to remember, next time you have a proprietary cable that’s gone missing.

![A Hackaday.io page screenshot, showing all the numerous CH552 projects from [Stefan].](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/hadimg_ch552_projects_feat.png?w=600&h=450)