Since the widespread adoption of USB 1.1 in the 90s, USB has become the de facto standard for connecting most peripherals to our everyday computers. The latest revision of the technology has been USB 4, which pushes the data rate capabilities to 40 Gbit/s. This amount of throughput is mindblowing compared to the USB 1.x speeds which were three to four orders of magnitude slower in comparison. But data speeds haven’t been the only thing changing with the USB specifications. The amount of power handling they can do has increased by orders of magnitude as well, as this DIY USB charger demonstrates by delivering around 200 W to multiple devices at once.

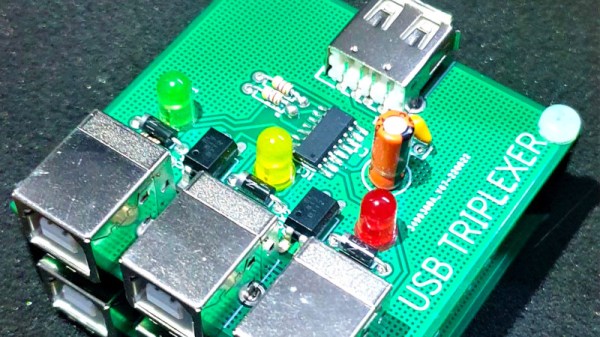

The build comes to us from [tobychui] who not only needed USB rapid charging for his devices while on-the-go but also wanted to build the rapid charger himself and for the charger to come in a small form factor while still using silicon components instead of more modern gallium nitride solutions. The solution he came up with was to use a 24 V DC power supply coupled with two regulator modules meant for solar panel installations to deliver a staggering amount of power to several devices at once. The charger is still relatively small, and cost around $30 US dollars to make.

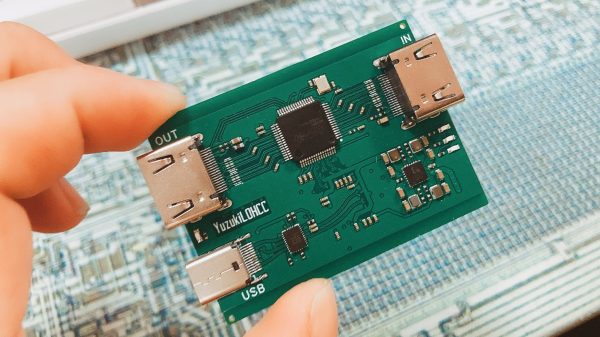

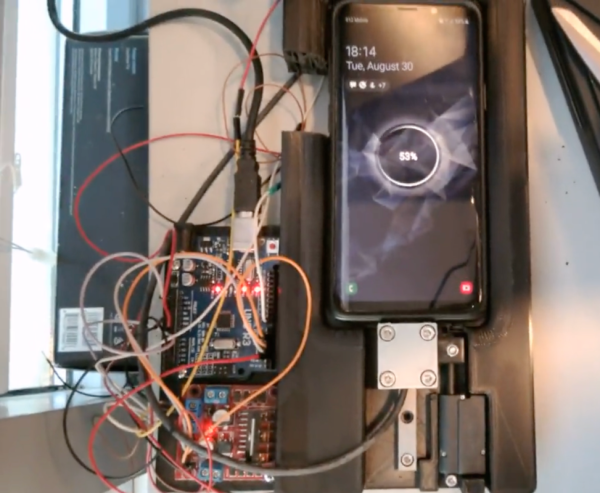

Part of what makes builds like this possible is the USB Power Delivery (PD) standard, which has enabled all kinds of electronics to switch to USB for their power needs rather than getting their power from dedicated, proprietary, and/or low-quality power bricks or wall warts. In fact, you can even use this technology to do things like charge lithium batteries.