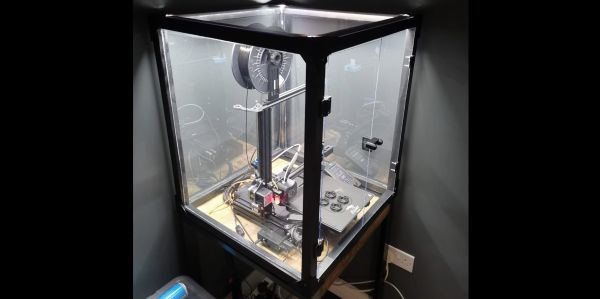

Having an enclosure around an FDM 3D printer is generally a good idea, even when printing only with PLA, as it keeps the noise in, and the heat (and smell, with ABS) inside. With all the available options for enclosures out there, however, [David McDaid] figured that it should be possible to make an enclosure that does not look like a grow tent and is not overly expensive. He also shared the design files on GitHub.

The essential idea is very simple and straightforward: the structural part is cut out of pine beams that are cut to size and joined into a cube by (3D-printed) corner brackets, with acrylic (Perspex) sheets filling in the space between the wooden beams. A door is formed using (also 3D-printed) hinges and door handles. The whole enclosure is rounded off with a lick of paint on the wooden elements, and a diffused set of LED lights for internal illumination.

It definitely has to be admitted that it makes for a very stylish enclosure, with a lot of modding potential. It can also easily be adapted to differently sized printers and filament material demands.

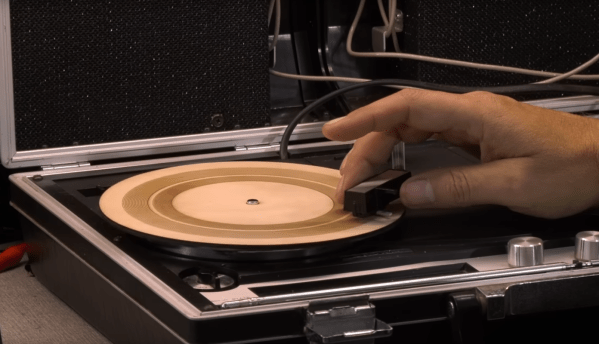

But ironically, this homage features a critical piece that’s actually not made of wood. The 77’s pickup pattern was cardioid, making for a directional mic that picked up sound best from the front, thanks to an acoustic labyrinth that increased the path length for incoming sound waves. [Frank]’s labyrinth was made from epoxy resin poured into a mold made from heavy paper, creating a cylinder with multiple parallel tunnels. The tops and bottoms of adjacent tunnels were connected together, creating an acoustic path over a meter long. The ribbon motor, as close to a duplicate of the original as possible using wood, sits atop the labyrinth block’s output underneath a wood veneer shell that does its best to imitate the classic pill-shaped windscreen of the original. The video below, which of course was narrated using the mic, shows its construction in detail.

But ironically, this homage features a critical piece that’s actually not made of wood. The 77’s pickup pattern was cardioid, making for a directional mic that picked up sound best from the front, thanks to an acoustic labyrinth that increased the path length for incoming sound waves. [Frank]’s labyrinth was made from epoxy resin poured into a mold made from heavy paper, creating a cylinder with multiple parallel tunnels. The tops and bottoms of adjacent tunnels were connected together, creating an acoustic path over a meter long. The ribbon motor, as close to a duplicate of the original as possible using wood, sits atop the labyrinth block’s output underneath a wood veneer shell that does its best to imitate the classic pill-shaped windscreen of the original. The video below, which of course was narrated using the mic, shows its construction in detail.