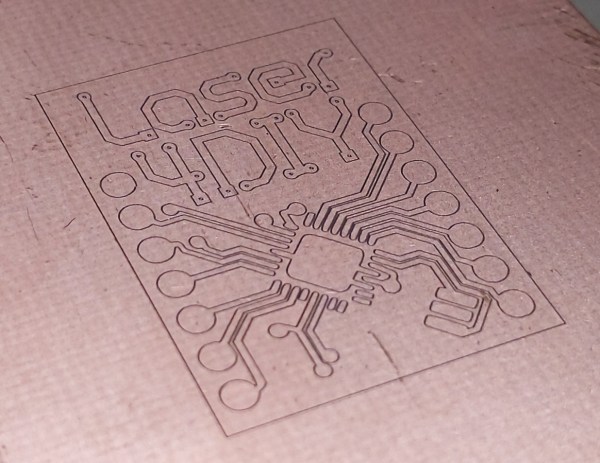

For those who wish to go beyond through-hole construction on perfboard for their circuit boards, a printed circuit board is usually the next step up. Allowing for things like surface-mount components, multi-layer boards, and a wider array of parts, they are much more versatile but do have a slight downside in that they are a little bit harder to make. There are lots of methods for producing them at home or makerspace, though, and although we’ve seen plenty of methods for their production like toner transfer, photoresist, and CNC milling, it’s also possible to make them using laser ablation, although you do need a special laser to get this job done.

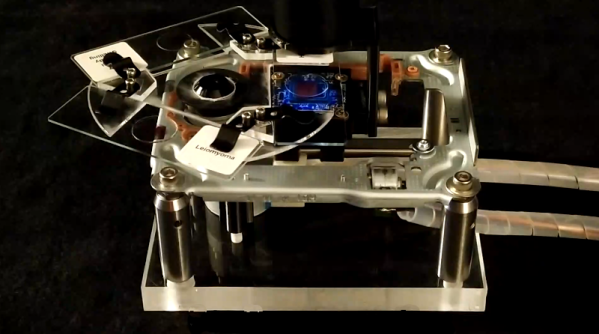

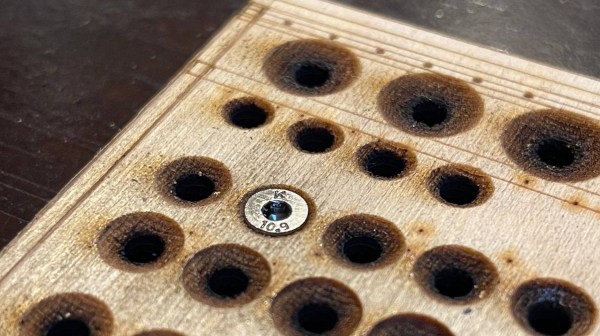

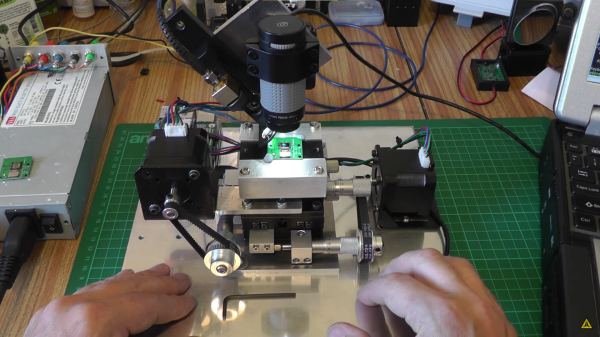

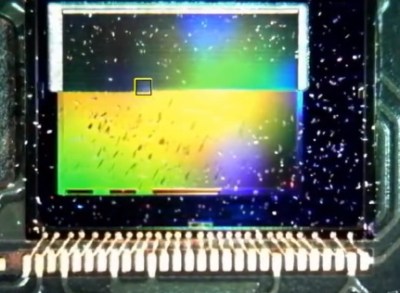

The problem with cutting copper is that it reflects infra-red, so a higher-wavelength blue green laser is used instead. And because you want to ablate the copper, but not melt the surrounding areas or cut straight through the board, extremely short, high-power pulses are the way to go. Here, the [Munich Fab Lab] is using 9 kW pulses of around 30 microseconds each. With these specifications the copper is ablated from the surface of the board allowing for fine details in the range of about 20 µm, which is fine enough for just about any circuit board. The design of the laser head itself is worth a look.

Aside from the laser, the rest is standard CNC machine fodder, but with an emphasis on safety that’s appropriate for a tool in a shared workspace, and the whole project is published under an open license and offers an affordable solution for larger-scale PCB production with extremely fine resolution and without the need for any amounts of chemicals for the more common PCB production methods. There is a lot more information available on the project’s webpage and its GitHub page as well.

Of course, there are other methods of producing PCBs by laser if you happen to have a 20 W fiber laser just kicking around.