Every time you watch a SpaceX livestream to see a roaring success or fireball on a barge (pick your poison), you probably see a few cubesats go up. Everytime you watch a Soyuz launch that is inexplicably on liveleak.com before anywhere else, you’re seeing a few cubesats go up. There are now hundreds of these 10 cm satellites in orbit, and SatNogs, the winner of the Hackaday Prize a two years ago, gives all these cubesats a global network of ground stations.

There is one significant problem with a global network of satellite tracking ground stations: you need to know the orbit of all these cubesats. This, as with all Low Earth Orbit deployments that do not have thrusters and rarely have attitude control, is a problem. These cubesats are tumbling through the rarefied atmosphere, leading to orbits that are unpredictable over several months.

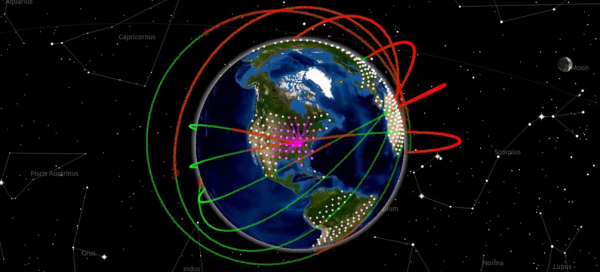

[hornig] is working on a solution to the problem of tracking hundreds of cubesats that is, simply, reverse GPS. Instead of using multiple satellites to determine a position on Earth, this system is using multiple receiving stations on Earth’s surface to determine the orbit of a satellite.

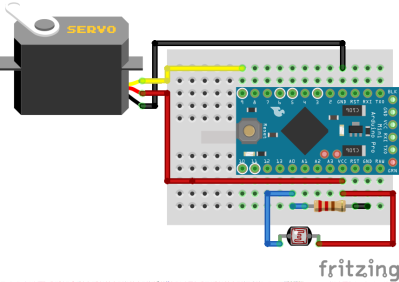

The hardware for [hornig]’s Distributed Ground Station Network is as simple as you would expect. It’s just an RTL-SDR TV tuner USB dongle, a few antennas, a GPS receiver, and a Raspberry Pi connected to the Internet. This device needs to be simple; unlike SatNogs, where single base station in the middle of nowhere can still receive data from cubesats, this system needs multiple receivers all within the view of a satellite.

The modern system of GPS satellites is one of the greatest technological achievements of all time. Not only did the US need to put highly accurate clocks in orbit, the designers of the system needed to take into account relativistic effects. Doing GPS in reverse – determining the orbit of satellites on the ground – is likewise a very impressive project, and something that is certainly a contender for this year’s Hackaday Prize.