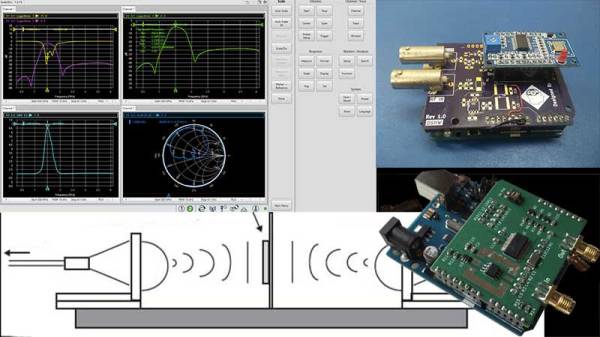

Instrumentation has progressed by leaps and bounds in the last few years, however, the fundamental analysis techniques that are the foundation of modern-day equipment remain the same. A network analyzer is an instrument that allows us to characterize RF networks such as filters, mixers, antennas and even new materials for microwave electronics such as ceramic capacitors and resonators in the gigahertz range. In this write-up, I discuss network analyzers in brief and how the DIY movement has helped bring down the cost of such devices. I will also share some existing projects that may help you build your own along with some use cases where a network analyzer may be employed. Let’s dive right in.

Network Analysis Fundamentals

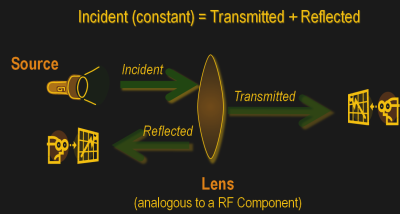

As a conceptual model, think of light hitting a lens and most of it going through but part of it getting reflected back.

As a conceptual model, think of light hitting a lens and most of it going through but part of it getting reflected back.

The same applies to an electrical/RF network where the RF energy that is launched into the device may be attenuated a bit, transmitted to an extent and some of it reflected back. This analysis gives us an attenuation coefficient and a reflection coefficient which explains the behavior of the device under test (DUT).

Of course, this may not be enough and we may also require information about the phase relationship between the signals. Such instruments are termed Vector Network Analysers and are helpful in measuring the scattering parameters or S-Parameters of a DUT.

The scattering matrix links the incident waves a1, a2 to the outgoing waves b1, b2 according to the following linear equation: .

The equation shows that the S-parameters are expressed as the matrix S, where and denote the output and input port numbers of the DUT.

This completely characterizes a network for attenuation, reflection as well as insertion loss. S-Parameters are explained more in details in Electromagnetic Field Theory and Transmission Line Theory but suffice to say that these measurements will be used to deduce the properties of the DUT and generate a mathematical model for the same.

General Architecture

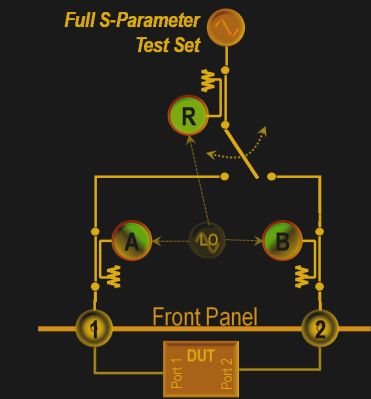

As mentioned previously, a simple network analyzer would be a signal generator connected and a spectrum analyzer combined to work together. The signal generator would be configured to output a signal of a known frequency and the spectrum analyzer would be used to detect the signal at the other end. Then the frequency would be changed to another and the process repeats such that the system sweeps a range of frequencies and the output can be tabulated or plotted on a graph. In order to get reflected power, a microwave component such as a magic-T or directional couplers, however, all of this is usually inbuilt into modern-day VNAs.

As mentioned previously, a simple network analyzer would be a signal generator connected and a spectrum analyzer combined to work together. The signal generator would be configured to output a signal of a known frequency and the spectrum analyzer would be used to detect the signal at the other end. Then the frequency would be changed to another and the process repeats such that the system sweeps a range of frequencies and the output can be tabulated or plotted on a graph. In order to get reflected power, a microwave component such as a magic-T or directional couplers, however, all of this is usually inbuilt into modern-day VNAs.

Continue reading “Network Analysers: The Electrical Kind”