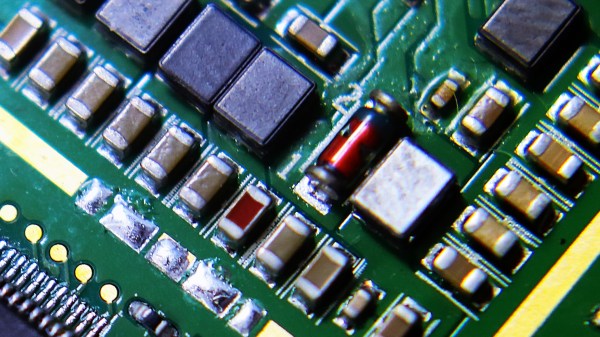

This morning Bloomberg is reporting a bombshell for hardware security. Companies like Amazon and Apple have found a malicious chip on their server motherboards. These are not counterfeit chips. They are not part of the motherboard design. These were added by the factory at the time of manufacture. The chip was placed among other signal conditioning components and is incredibly hard to spot as the nature of these motherboards includes hundreds of minuscule components.

Though Amazon and Apple have denied it, according to Bloomberg, a private security contractor in Canada found the hidden chip on server motherboards. Elemental Technologies, acquired by Amazon in 2015 for its video and graphics processing hardware, subcontracted Supermicro (Super Micro Computer, Inc.) to manufacture their server motherboards in China. It is unknown how many of the company’s products have this type of malicious hardware in them, equipment from Elemental Technologies has been supplied to the likes of government contractors as well as major banks and even reportedly used in the CIA’s drone operations.

How the Hack Works

The attacks work with the small chip being implanted onto the motherboard disguised as signal couplers. It is unclear how the chip gains access to the peripherals such as memory (as reported by Bloomberg) but it is possible it has something to do with accessing the bus. The chip controls some data lines on the motherboard that likely provide an attack vector for the baseboard management controller (BMC).

Hackaday spoke with Joe FitzPatrick (a well known hardware security guru who was quoted in the Bloomberg article). He finds this reported attack as a very believable approach to compromising servers. His take on the BMC is that it’s usually an ARM processor running an ancient version of Linux that has control over the major parts of the server. Any known vulnerability in the BMC would be an attack surface for the custom chip.

Data centers house thousands of individual servers that see no physical interaction from humans once installed. The BMC lets administrators control the servers remotely to reboot malfunctioning equipment among other administrative tasks. If this malicious chip can take control of the BMC, then it can provide remote access to whomever installed the chip. Reported investigations have revealed the hack in action with brief check-in communications from these chips though it’s difficult to say if they had already served their purpose or were being saved for a future date.

What Now?

Adding hardware to a design is fundamentally different than software-based hacking: it leaves physical evidence behind. Bloomberg reports on US government efforts to investigate the supply chain attached to these parts. It is worth noting though that the article doesn’t include any named sources while pointing the finger at China’s People’s Liberation Army.

The solution is not a simple one if servers with this malicious chip were already out in the field. Even if you know a motherboard has the additional component, finding it is not easy. Bloomberg also has unconfirmed reports that the next-generation of this attack places the malicious component between layers of the circuit board. If true, an x-ray would be required to spot the additional part.

A true solution for high-security applications will require specialized means of making sure that the resulting product is not altered in any way. This hack takes things to a whole new level and calls into question how we validate hardware that runs our networks.

Update: We changed the penultimate paragraph to include the word if: “…simple one if servers with…” as it has not been independently verified that servers were actually out in the field and companies have denied Bloomberg’s reporting that they were.

[Note: Image is a generic photo and not the actual hardware]