Perlin noise is best explained in visual terms: if a 2D slice of truly random noise looks like even and harsh static, then a random 2D slice of Perlin noise will have a natural-looking blotchy structure, with smooth gradients. [Jacob Stanton] used Perlin noise as the starting point for creating some interesting generative vector art that shows off all kinds of different visuals. [Jacob] found that his results often exhibited a natural quality, with the visuals evoking a sense of things like moss, scales, hills, fur, and “other things too strange to describe.”

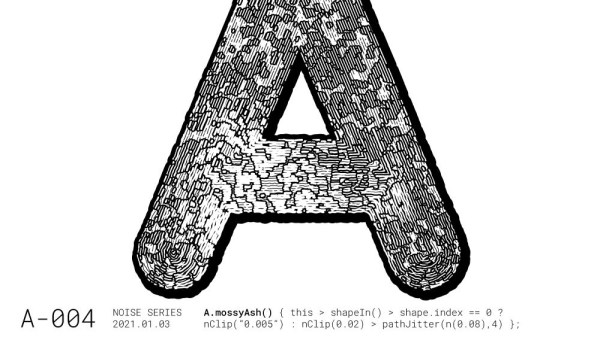

The art project [Jacob] created from it all is a series of posters showcasing some of the more striking examples, each of which displays an “A” modified in a different way. A few are shown here, and a collection of other results is also available.

The art project [Jacob] created from it all is a series of posters showcasing some of the more striking examples, each of which displays an “A” modified in a different way. A few are shown here, and a collection of other results is also available.

Perlin noise was created by Ken Perlin while working on the original Tron movie in the early 80s, and came from a frustration with the look of computer generated imagery of the time. His work had a tremendous and lasting impact, and was instrumental to artists creating more natural-looking textures. Processing has a Perlin noise function, which was in fact [Jacob]’s starting point for this whole project.

Noise, after all, is a wide and varied term. From making generative art to a cone of silence for smart speakers, it has many practical and artistic applications.

This began by collecting 150 pounds (!) of magnetic dirt from dry lake beds while hiking using a magnet pickup tool with release lever that he got from Harbor Freight. Several repeated magnetic refining passes separated the black ore from non-metallic sands ready for the furnace that he built. That is used to fire up the raw materials using 150 pounds of charcoal, changing the chemical composition by adding carbon and resulting in a gnarly lump of iron

This began by collecting 150 pounds (!) of magnetic dirt from dry lake beds while hiking using a magnet pickup tool with release lever that he got from Harbor Freight. Several repeated magnetic refining passes separated the black ore from non-metallic sands ready for the furnace that he built. That is used to fire up the raw materials using 150 pounds of charcoal, changing the chemical composition by adding carbon and resulting in a gnarly lump of iron