Wired and SCMP are reporting on interesting trivia from the realm of chip shortages. Apparently, some large conglomerate out there is buying new washing machines and scavenging the chips they can’t obtain otherwise. My imagination pictures skilled engineers in a production room, heavy-duty electric screwdrivers and desoldering toolkits on the floor next to them, and a half-torn-down washing machine about to reveal its control board with an STM32 right in the middle. This might not be the most skilled job, but it’s a change of pace, and hey, as long as the rate stays the same?

Whichever company is doing this, they’re in a conundrum for sure. One of the articles offers an example of a $350,000 spectrometer manufacturing being stalled by lack of a $0.50 part – while this feels exaggerated, it’s within the realm of possibility. For car manufacturers, the difference isn’t as dire, but still severe enough, and not meeting the production targets has ramifications other than the financial ones. It might indeed make sense to buy a $150 washing machine in order to finally be able to move a $30,000 car off the assembly line.

Continue reading “Companies Rumored To Harvest Washing Machines For ICs”

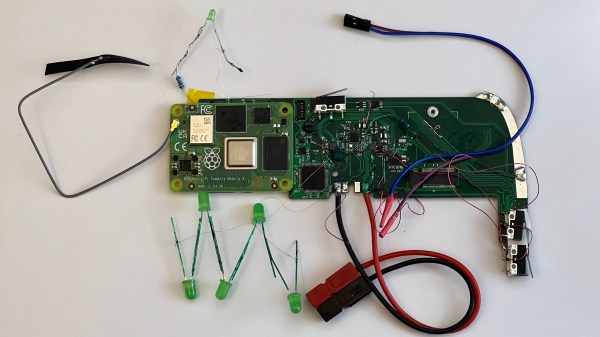

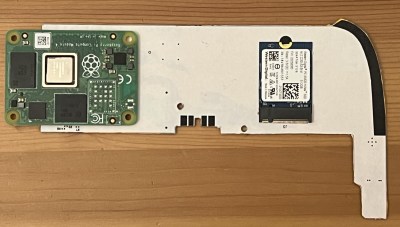

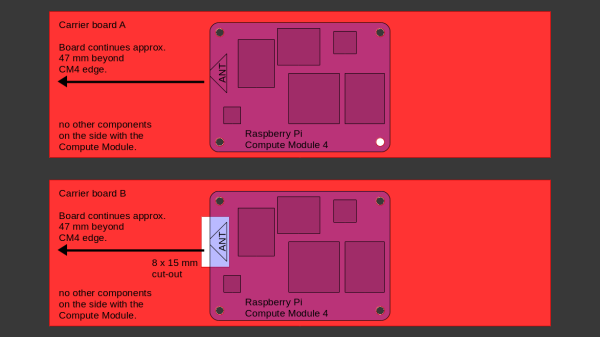

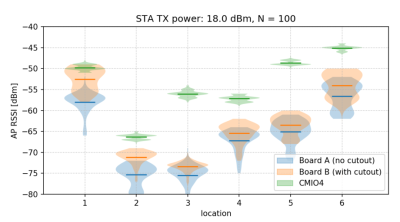

After setting up some test locations and writing a few scripts for ease of testing, [Avian] recorded the experiment data. Having that data plotted, it would seem that, while presence of an under-antenna cutout helps, it doesn’t affect RSSI as much as the module placement does. Of course, there’s way more variables that could affect RSSI results for your own designs – thankfully, the scripts used for logging are available, so you can test your own setups if need be.

After setting up some test locations and writing a few scripts for ease of testing, [Avian] recorded the experiment data. Having that data plotted, it would seem that, while presence of an under-antenna cutout helps, it doesn’t affect RSSI as much as the module placement does. Of course, there’s way more variables that could affect RSSI results for your own designs – thankfully, the scripts used for logging are available, so you can test your own setups if need be.

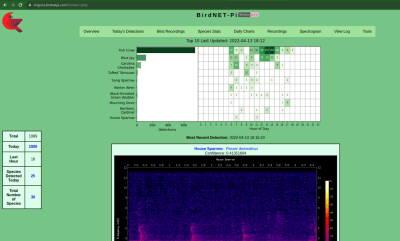

About that Raspberry Pi version! There’s a sister project called

About that Raspberry Pi version! There’s a sister project called