When working with limited space or even with limited funding, finding a tool that can do many things for less space or cost than its separate counterparts is a tempting option. The most common downside is that these tools often can’t perform as well as the single-purpose tools they replace, with the obvious example being a pocket-sized multitool or Swiss Army knife. Even things like combination drill and driver tools, adjustable crescent wrenches, or even a kitchen stand mixer can’t quite perform as well as their dedicated counterparts. So when we find a tool that can do two things equally well, like this rock tumbler that can also make a delicious bowl of ice cream, it’s definitely noteworthy.

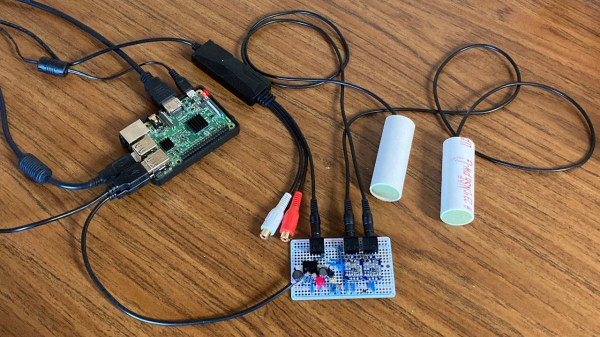

The project comes to us by way of [North_Stordeur] whose main goal was to create a delicious bowl of ice cream but was deterred by the cost of purpose-built ice cream makers. Making ice cream isn’t a particularly complex process, though, and [North_Stordeur ] realized that grinding down ice for ice cream shares similarities with tumbling and polishing rocks. Normally, the rocks to be polished are placed in a drum with grit and a liquid, then the drum is placed on the tumbler and spun, which causes the rocks to bounce around inside the drum with the grit and smooth out relatively quickly. Replacing sugar for grit, ice for rocks, and milk for the liquid, the ice eventually is worn all the way down, creating an excellent bowl of ice cream.

Truly, the only downside we could see with a build like this is that the drum in the National Geographic rock tumbler that [North_Stordeur] chose for this project looks like it would only make a single serving at a time. However, with picky eaters around who like their own additions to ice cream, this might be a perk as everyone can make exactly the style they like with their own choice of flavors. It’s an excellent discovery for anyone already grinding and polishing rocks or someone who has already built a DIY ball mill for any number of other uses.