Almost all entry-level physics courses, and even some well into a degree program, will have the student make some assumptions in order to avoid some complex topics later on. Most commonly this is something to the effect of “ignore the effects of wind resistance” which can make an otherwise simple question in math several orders of magnitude more difficult. At some point, though, wind resistance can’t be ignored any more like when building this remote-controlled car designed for extremely high speeds.

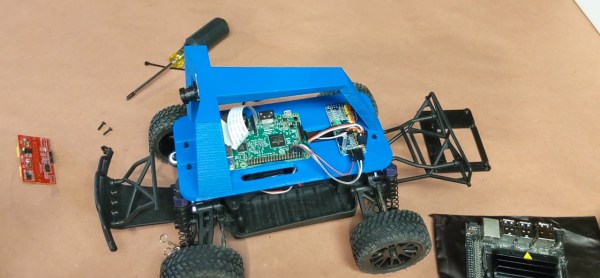

[Indeterminate Design] has been working on this project for a while now, and it’s quite a bit beyond the design of most other RC cars we’ve seen before. The design took into account extreme aerodynamics to help the car generate not only the downforce needed to keep the tires in contact with the ground, but to keep the car stable in high-speed turns thanks to its custom 3D printed body. There is a suite of high-speed sensors on board as well which help control the vehicle including four-wheel independent torque vectoring, allowing for precise control of each wheel. During initial tests the car has demonstrated its ability to corner at 2.6 lateral G, a 250% increase in corning speed over the same car without the aid of aerodynamics.

We’ve linked the playlist to the entire build log above, but be sure to take a look at the video linked after the break which goes into detail about the car’s aerodynamic design specifically. [Indeterminate Design] notes that it’s still very early in the car’s development, but has already exceeded the original expectations for the build. There are also some scaled-up vehicles capable of transporting people which have gone to extremes in aerodynamic design to take a look at as well.

Continue reading “Remote-Controlled Hypercar Slices Through Air”