An open-source canine training research tool was just been released by [Walker Arce] and [Jeffrey Stevens] at the University of Nebraska — Lincoln’s Canine Cognition and Human Interaction Lab (C-CHIL).

We didn’t realize that dog training research techniques were so high-tech. Operant conditioning, as opposed to Pavlovian, gives a positive reward, in this case dog treats, to reinforce a desired behavior. Traditionally operant conditioning involved dispensing the treat manually and some devices do exist using wireless remote controls, but they are still manually operated and can give inconsistent results (too many or too few treats). There weren’t any existing methods available to automate this process, so this team decided to rectify the situation.

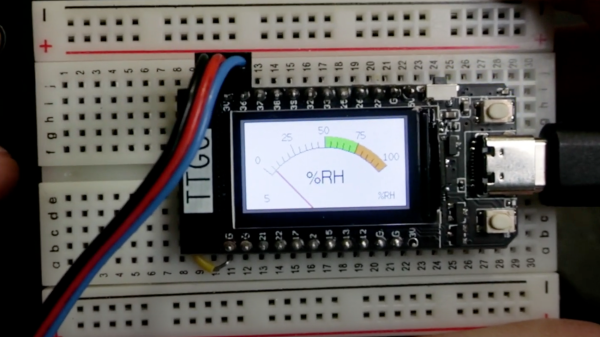

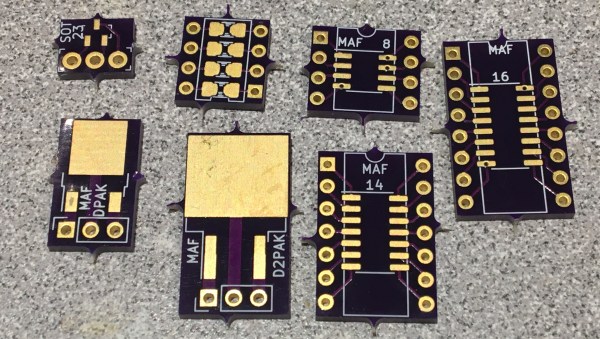

They took a commercial treat dispenser and retro-fitted it with an interface board that taps into the dispenser’s IR sensors to detect that the hopper is moving and treats were actually dispensed. The interface board connects to a Raspberry Pi which serves as a full-featured platform to run the tests. In this demonstration it connects to an HDMI monitor, detecting touches from the dog’s nose to correlate with events onscreen. Future researchers won’t have to reinvent the wheel, just redesign the test itself, because [Walker] and [Jeffrey] have released all the firmware and hardware as open-source on the lab’s GitHub repository.

In the short video clip below, watch the dog as he gets a treat when he taps the white dot with his snout. If you look closely, at one point the dog briefly moves the mouse pointer as well. We predict by next year the C-CHIL researchers will have this fellow drawing pictures and playing checkers.