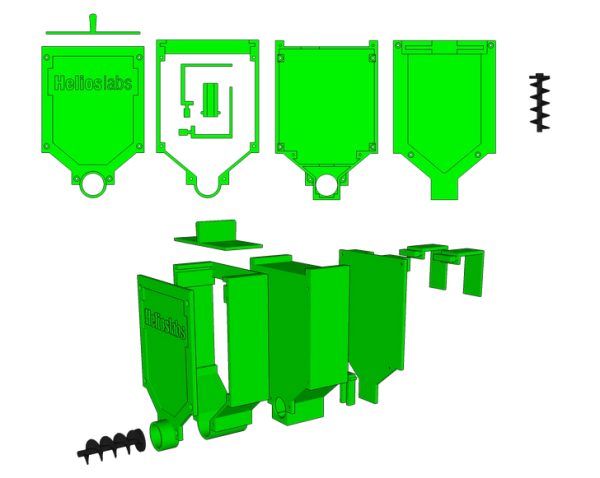

[Bayres’] dad setup a webcam as a surveillance camera for a remote property. The only problem was that the only stable Internet connection they could get at this property was DSL. This meant that the external IP address of the webcam would change somewhat often; the needed a way to keep track of the external IP address whenever it changed. That’s when [Bayres] built a solution using Arduino and an Ethernet shield.

The main function of this device is to monitor the public IP address and report any changes. This is accomplished by first making a request to checkip.dyndns.org. This website simply reports your current public IP address. [Bayres] uses an Arduino library called Textfinder in order to search through the returned string and identify the IP address.

From there, the program compares this current value to the previous one. If there is any change, the program uses the Sendmail() function to reach out to an SMTP server and send an e-mail alert to [Beyres’] dad. The system also includes a small LCD. The Arduino outputs the current IP address to this display, making it easy to check up on the connection. The LCD is driven by 74HC595 shift register in order to conserve pins on the Arduino.

The system is also designed with a pretty slick setup interface. When it is booted, the user can enter a configuration menu via a Serial terminal. This setup menu allows the user to configure options such as SMTP server, email address, etc. These variables are then edited and can be committed to EEPROM as a more permanent storage solution. Whenever the system is booted, these values are read back out of the EEPROM and returned to their appropriate variables. This means you can reconfigure the device on the fly without having to edit the source code and re-upload.