This deep dive into the Linux-powered Reolink B800 IP camera started because of a broken promise from its manufacturer. When [George Hilliard] purchased a kit that included six of the cameras and a video recorder, the website said they were capable of outputting standard RTSP video. But once he took delivery of the goods, and naturally after his return window had closed, the site was updated to say that the cameras can only function with the included recorder.

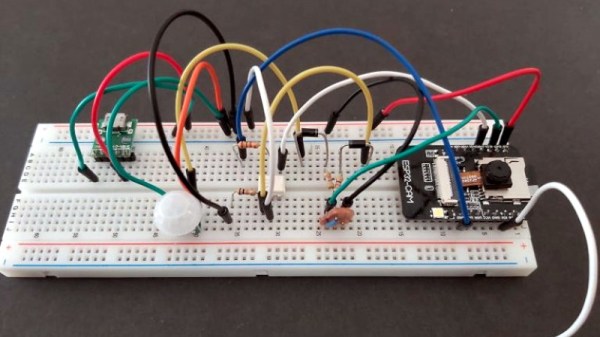

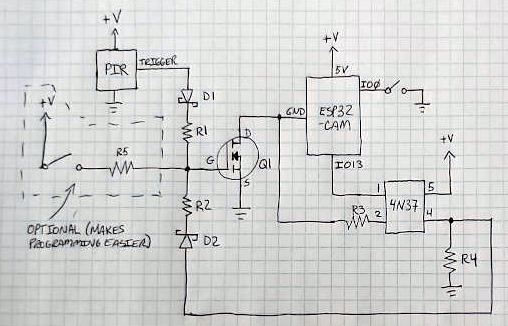

Taking that as something of challenge, [George] got to work. His first big break came when he desoldered the camera’s SPI flash chip and replaced it with a socket. That allowed him to easily take the chip out of the device for reading and flashing as he tinkered with modifying the firmware. After adding cross-compiled versions of

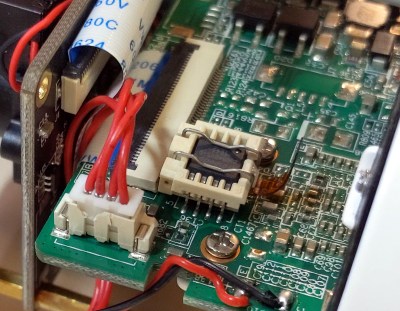

Taking that as something of challenge, [George] got to work. His first big break came when he desoldered the camera’s SPI flash chip and replaced it with a socket. That allowed him to easily take the chip out of the device for reading and flashing as he tinkered with modifying the firmware. After adding cross-compiled versions of busybox, gdb, and strace to the extracted firmware, he bundled it back up and flashed it back to the hardware.

If you think that’s the end of the story, it isn’t. In fact, it’s just the beginning. While getting root-level access to the camera’s OS would have potentially allowed for [George] to dump all the proprietary software it was running and replace it with open alternatives, he decided to take a different approach.

Instead of replacing the camera’s original software, he used his newly granted root powers to analyze it and figure out how it worked. This allowed for to sniff out some very suspect “encryption” routines built into the software, and eventually write his own server side in Rust that finally allowed him to use the cameras with his own server…albeit with a bit more work than he bargained for.

Projects like these are a fantastic look at real world reverse engineering, and a reminder that sometimes achieving your ultimate goal means taking the long way around. Even if you’re not in the market for a hacked security camera, there’s no doubt that reading the thorough write-up [George] has prepared will teach you a few things. But of course, we’d expect no less from a guy who runs Linux on his business card.