In the era of touch screens and capacitive buttons, we’d be lying if we said we didn’t have the occasional pang of nostalgia for the good old days when interfacing with devices had a bit more heft to it. The physical clunk and snap of switches never seems to get old, and while you can always pick up a mechanical keyboard for your computer if you want to hear that beautiful staccato sound while firing off your angry Tweets, there’s a definite dearth of mechanical interface devices otherwise.

[Jeremy Cook] decided to take matters into his own hands (literally and figuratively) by designing his own multipurpose USB rotary input device. It’s not a replacement for the mouse or keyboard, but a third pillar of the desktop which offers a unique way of controlling software. It’s naturally suited to controlling things like volume or any other variable which would benefit from some fine tuning, but as demonstrated in the video after the break even has some gaming applications. No doubt the good readers of Hackaday could think of even more potential applications for a gadget like this.

[Jeremy Cook] decided to take matters into his own hands (literally and figuratively) by designing his own multipurpose USB rotary input device. It’s not a replacement for the mouse or keyboard, but a third pillar of the desktop which offers a unique way of controlling software. It’s naturally suited to controlling things like volume or any other variable which would benefit from some fine tuning, but as demonstrated in the video after the break even has some gaming applications. No doubt the good readers of Hackaday could think of even more potential applications for a gadget like this.

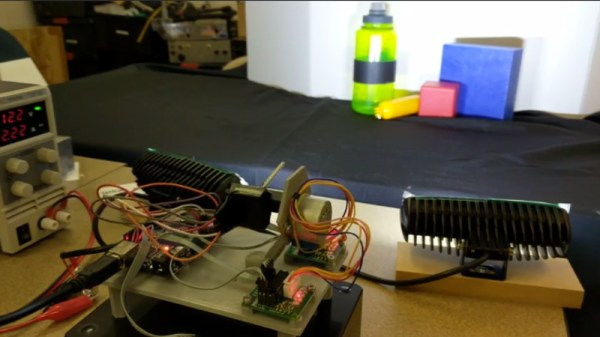

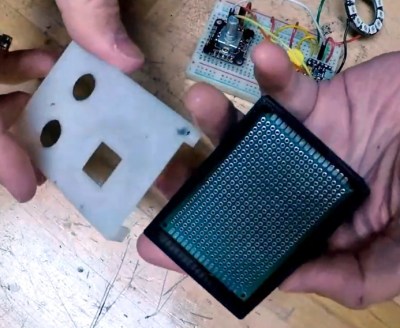

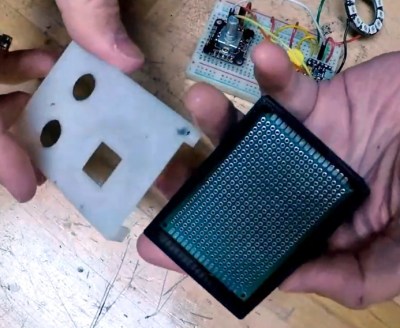

The device is built around the diminutive Arduino-compatible PICO board by MellBell, which features a ATmega32u4 and native USB. This allowed him to very rapidly spin up a USB Human Interface Device (HID) with minimal headaches, all he had to do was hang his buttons and rotary encoder on the PICO’s digital pins. To that end, he [Jeremy] used the fantastic I2C rotary encoder designed by [fattore.saimon], which readers may remember as a finalist in the Open Hardware Design Challenge phase of the 2018 Hackaday Prize. He also added a NeoPixel ring around the encoder to use for some visual feedback and because, well, it just looks cool.

Since all of the core components are digital, there’s not a whole lot required in the way of wiring or passive components. This let [Jeremy] put the whole thing together on a piece of perfboard, freeing him up to spend time designing the 3D printed enclosure complete with translucent lid so he can see the NeoPixel blinkenlights. He got the tolerances tight enough that the whole device can be neatly press-fit together, and even thought to add holes in the bottom of the case so he could push the perfboard back out if he needed to down the line.

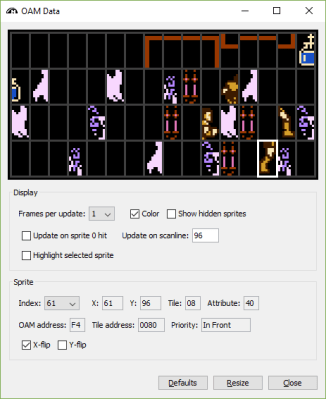

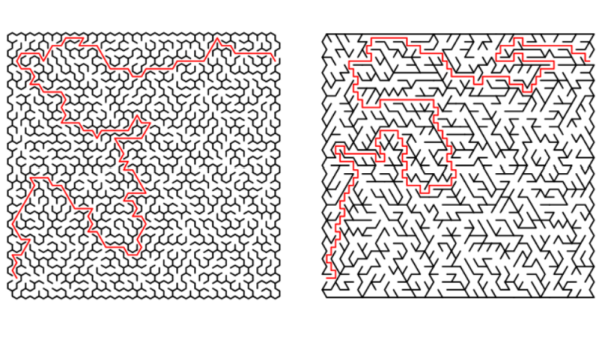

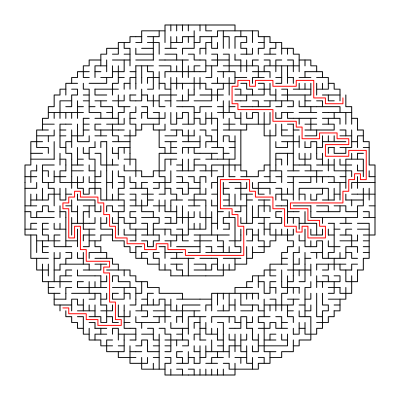

[Jeremy] spends a good chunk of the video going over the software setup and development of the firmware, and details some of the nuances he had to wrap his head around when working with the I2C encoder. He also explains the math involved in getting his encoder to emulate a mouse cursor moving in a circle, which he thinks could be useful when emulating games that originally used an encoder such as Tempest or Pong.

We’ve seen similar USB “knobs” in the past for controlling volume, but the additional inputs that [Jeremy] built into his version definitely makes it a bit more practical. Of course we’re suckers for interesting USB input devices to begin with.

Continue reading “Every Computer Deserves A Rotary Encoder” →