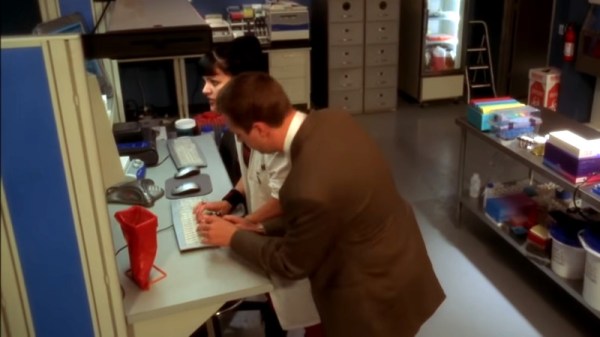

We imagine many of you have seen the ridiculous scene from the TV series NCIS in which a network intrusion is combated by two people working at the same keyboard at once. It’s become a meme in our community, and it’s certainly quite funny. But could there be a little truth behind the unintentional joke? [Tedu] presents some possibilities, and they’re not all either far-fetched or without application.

The first is called Duelmon, and it’s a split-screen process and network monitor worthy of two players, while the second is Mirrorkeys, a keyboard splitter which uses the Windows keys as modifiers to supply the missing half. As they say, the ability to use both at once would be the mark of the truly 1337.

Meanwhile here at Hackaday we’re evidently closer to 1336.5, as our pieces are written by single writers alone at the keyboard. We would be fascinated to see whether readers could name any other potential weapons in the dual-hacker arsenal though, and we’d like to remind you that as always, the comments are open below.

The intense hacking scene from NCIS can be found below the break. Be warned though, it contains the trauma of seeing a computer unplugged without shutting down first.

Continue reading “Only One Hacker At The Keyboard? Amateurs!”