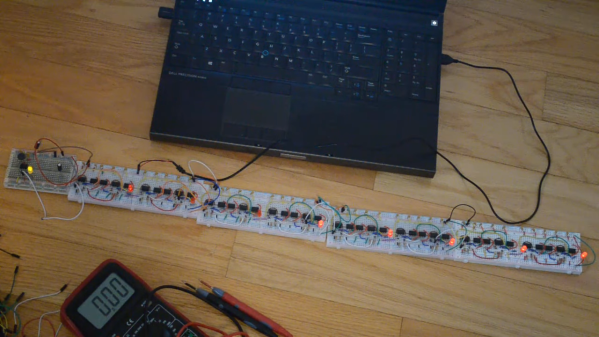

There’s a lot to admire about LED matrix projects, which more often than not end up looking really cool. But most of them rely on RGB matrix panels sourced from the surplus market, and while there’s nothing wrong with that, building your own tiny, tileable LED matrix panels makes these builds just a little bit cooler.

There’s a lot to admire about these matrix panels, not least of which is the seamless way they tile together. But to get to that point, [sjm4306] had a lot of prep work to do. He started with a much simpler 5×7 array, using the popular WS2812 RGB LEDs on a custom PCB. With a little practice under his belt, it was time to move to the much smaller SK6805 LEDs, which were laid out in an 8×8 matrix. The board layout is about as compact as it can be; [sjm4306] reports that it pushed the PCB fab to their limits, but he ended up with LEDs spaced perfectly on the board and just enough margin to keep consistent spacing in two dimensions when the boards are adjacent to each other.

Assembly of the boards was challenging, to say the least. The video below shows that the design left barely enough room for handling the LEDs with tweezers, and some fancy finagling was needed to get the boards on and off the hotplate for reflow. [sjm4306] says that he’ll be exploring JLC PCB’s assembly service in the future, since each board took an hour for him to assemble. But they look fantastic when daisy-chained together, with no detectable gaps at the joints.

With matrices like these, the possibilities are endless. We’ve even got a whole list of LED matrix projects over on Hackaday.io for you to check out.

Continue reading “Tiny LED Matrix Panels Tile Together Perfectly”

Unbinare’s tools are designed to work in harmony with each other, a requirement for any productive reverse-engineering effort. OI!STER is a general-purpose salvaged MCU research board, with sockets to adapt to different TQFP chip sizes. This board is Maurits’s experience in reverse-engineering condensed into a universal tool, including a myriad of connectors for different programming/debugging interfaces. We don’t know the board’s full scope, but the pictures show an STM32 chip inside the TQFP socket, abundant everywhere except your online retailer of choice. Apart from all the ways to break out the pins, OI!STER has sockets for power and clock glitching, letting you target these two omnipresent Achilles’ heels with a tool like ChipWhisperer.

Unbinare’s tools are designed to work in harmony with each other, a requirement for any productive reverse-engineering effort. OI!STER is a general-purpose salvaged MCU research board, with sockets to adapt to different TQFP chip sizes. This board is Maurits’s experience in reverse-engineering condensed into a universal tool, including a myriad of connectors for different programming/debugging interfaces. We don’t know the board’s full scope, but the pictures show an STM32 chip inside the TQFP socket, abundant everywhere except your online retailer of choice. Apart from all the ways to break out the pins, OI!STER has sockets for power and clock glitching, letting you target these two omnipresent Achilles’ heels with a tool like ChipWhisperer.