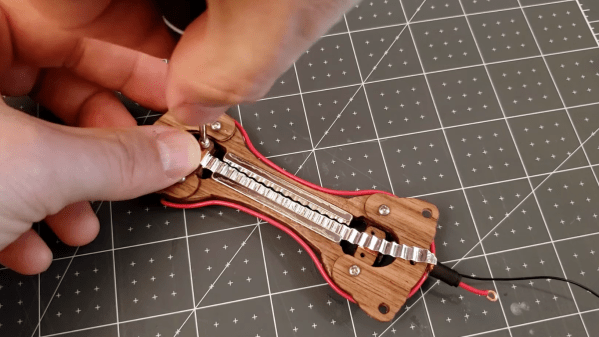

The Dreamcast is a somewhat forgotten console today, but for a shining minute in the late 1990s, it was possible to believe Sega were still in the fight. Regardless, their hardware lives on, lovingly preserved by collectors and enthusiasts. [Nicholas FitzRoy-Dale] is one such enthusiast, and set about interfacing the old console’s controllers to an Arduino.

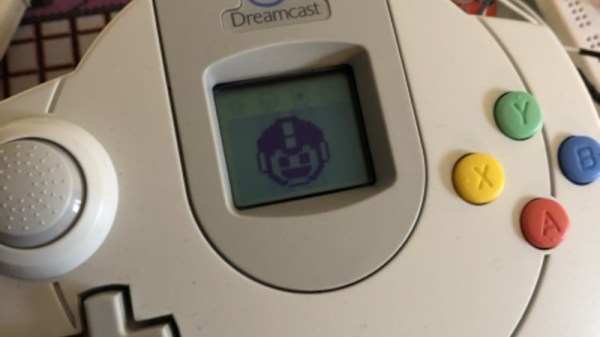

Initial work involved getting the Arduino (presumably a basic 16 Mhz Uno) to read the controller’s buttons, and spitting the data out over serial. The Dreamcast’s Maple bus is fast, which presented some challenges, but it was simple enough. [Nicholas] then moved on to interfacing the VMU, the Dreamcast’s fancy controller-mounted memory card. After initial attempts were shaky and unstable, he redoubled his efforts. Research indicated that the VMU can vary the speed of the bus when it’s in control, so he updated his code to suit. It’s full of great hacks, like connecting the Dreamcast’s two data pins to four input pins on the Arduino, to save a handful of cycles by not having to shift incoming data.

The work is a great read for anyone into assembly-level optimisation of interfaces, as well as proper use of limited resources. Obviously, it’s easy to just throw a faster, more expensive microcontroller at the problem, but then nobody would have learned anything. We’ve featured a great many Dreamcast hacks over the years; [Nicholas]’s work here builds upon [Dmitry]’s work in 2017. We can’t wait to see what comes next out of the underground Sega hacking scene!