A couple of weeks ago, Linus Torvalds laid down the law, in a particularly Linusesque sort of way. In a software community where tabs vs. spaces can start religious wars, saying that 80-character-wide code was obsolete was, to some, utter heresy. For more background on how we got here, read [Sven Gregori]’s history piece on Hackaday, and you’ll learn that sliced bread and the 80-character IBM punch card both made their debut in July, 1928. But I digress.

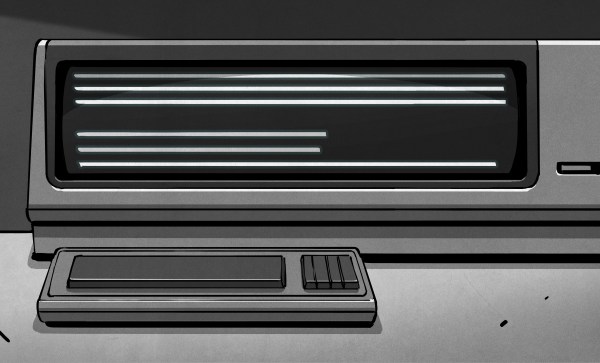

When I look at a codebase, I like to see its structure, and I’m not alone. That’s one of the reasons for the Linux Kernel style guide’s ridiculously wide 8-character tabs. Combined with a trend for variable names becoming more and more descriptive, which I take to be a good thing, and monitors’ aspect ratios growing seemingly without end, which I don’t, the 80-column width seems like a relic from the long-gone era of the VT-220.

In Linus’ missive, we learn that he runs terminals at 100 x 50, and frequently drags them out to a screen-filling 142 x 76. (Amateur! I write this to you now on 187 x 48.) When you’re running this wide, it doesn’t make any sense to line-wrap argument lists, even if you’re using Hungarian notation.

In Linus’ missive, we learn that he runs terminals at 100 x 50, and frequently drags them out to a screen-filling 142 x 76. (Amateur! I write this to you now on 187 x 48.) When you’re running this wide, it doesn’t make any sense to line-wrap argument lists, even if you’re using Hungarian notation.

And yet, change is painful. I’ve had to re-format code to meet 73-column restrictions for a book, only to discover that my inline comments were too verbose. Removing even an artificial restriction like the 80-column limit will have real effects. I write longer paragraphs, for instance, on a wider screen.

I see a few good things to come out of this, though. If single thoughts can be expressed on single lines, it makes the shape of the code better reflect its function. Getting rid of pointless wrapping takes up less vertical space, which is at a premium on today’s cinematic monitors. And if it makes inline comments better (I know, another holy war!) or facilitates better variable naming, it will have been worth it.

But any way you slice it, we’re no longer typing on the old 80-character Hazeltine. It’s high time for our coding style and practice to catch up.