To the surprise of nobody with the slightest bit of technical intuition or just plain common sense, the world’s first solar roadway has proven to be a complete failure. The road, covering one lane and stretching all of 1,000 meters across the Normandy countryside, was installed in 2016 to great fanfare and with the goal of powering the streetlights in the town of Tourouvre. It didn’t even come close, producing less than half of its predicted power, due in part to the accumulation of leaves on the road every fall and the fact that Normandy only enjoys about 44 days of strong sunshine per year. Who could have foreseen such a thing? Dave Jones at EEVBlog has been all over the solar freakin’ roadways fiasco for years, and he’s predictably tickled pink by this announcement.

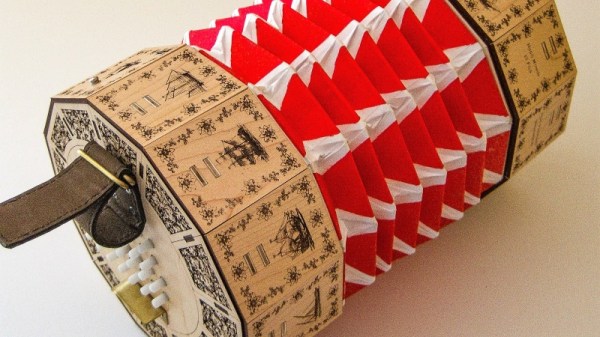

I’m not going to admit to being the kid in grade school who got bored in class and regularly filled pages of my notebook with all the binary numbers between 0 and wherever I ran out of room – or got caught. But this entirely mechanical binary number trainer really resonates with me nonetheless. @MattBlaze came up with the 3D-printed widget and showed it off at DEF CON 27. Each two-sided card has an arm that flops down and overlaps onto the more significant bit card to the left, which acts as a carry flag. It clearly needs a little tune-up, but the idea is great and something like this would be a fun way to teach kids about binary numbers. And save notebook paper.

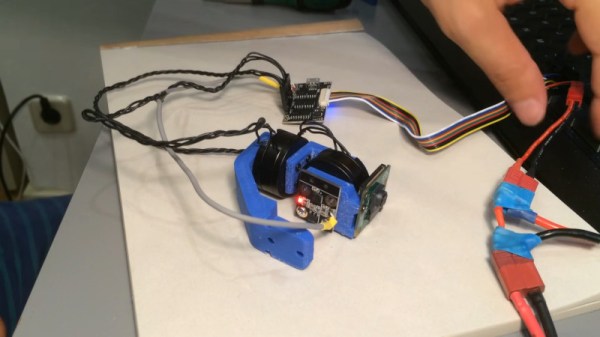

Is that a robot in your running shorts or are you just sporting an assistive exosuit? In yet another example of how exoskeletons are becoming mainstream, researchers at Harvard have developed a soft “exoshort” to assist walkers and runners. These are not a hard exoskeleton in the traditional way; rather, these are basically running short with Bowden cable actuators added to them. Servos pull the cables when the thigh muscles contract, adding to their force and acting as an aid to the user whether walking or running. In tests the exoshorts resulted in a 9% decrease in the amount of effort needed to walk; that might not sound like much, but a soldier walking 9% further on the same number of input calories or carrying 9% more load could be a big deal.

In the “Running Afoul of the FCC” department, we found two stories of interest. The first involves Jimmy Kimmel’s misuse of the Emergency Alert System tones in an October 2018 skit. The stunt resulted in a $395,000 fine for ABC, as well as hefty fines for two other shows that managed to include the distinctive EAS tones in their broadcasts, showing that the FCC takes very seriously indeed the integrity of a system designed to warn people of their approaching doom.

The second story from the regulatory world is of a land mobile radio company in New Jersey slapped with a cease and desist order by the FCC for programming mobile radios to use the wrong frequency. The story (via r/amateurradio) came to light when someone reported interference from a car service’s mobile radios; subsequent investigation showed that someone had programmed the radios to transmit on 154.8025 MHz, which is 5 MHz below the service’s assigned frequency. It’s pretty clear that the tech who programmed the radio either fat-fingered it or misread a “9” as a “4”, and it’s likely that there was no criminal intent. The FCC probably realized this and didn’t levy a fine, but they did send a message loud and clear, not only to the radio vendor but to anyone looking to work frequencies they’re not licensed for.