Drop what you’re doing and get thee to thy workshop. This is the last weekend of the Hackaday Circuit Sculpture Contest, the perfect chance for you to exercise the creative hacker within by building something artistic using stuff you already have on hand.

The concept is simple: build a sculpture where the electronic circuit is the sculpture. Wire the components up in a way that shows off that wiring, and uses it as the structure of the art piece. Seven top finishers will win prizes, but really we want to see everyone give this a try because the results are so cool! Need proof? Check out all the entries, then ooh and ah over a few we’ve picked out below. You have until this Tuesday at noon Pacific time to get in the game.

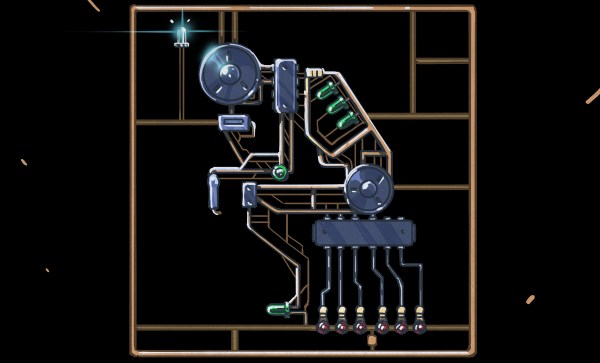

These are just three awesome examples of the different styles we’ve seen so far in the contest. Who needs a circuit board for a retro computer? Most people… but apparently not [Matseng] as this Z80 computer is freformed yet still interactive.

Really there can’t be many things more horrifying than the thought of spider robots, but somehow [Sunny] has taken away all of our fears. The 555 spider project takes “dead bug” to a whole new level. We love the angles in the legs, and the four SMD LEDs as spider eyes really finish the look of the tiny beast.

Finally, the 3D design of [Emily Valesco’s] RGB Atari Punk Console is spectacular. It’s a build that sounds great, and looks as though it will hold up to regular use. But visually, this earns a place on your desk long after the punky appeal wears off. We also like it that she added a color-coded photograph to match up the structure to the schematic, very cool!

What are you waiting for, whether it’s a mess of wires or a carefully structured electron ballet, we want to see your Circuit Sculpture!

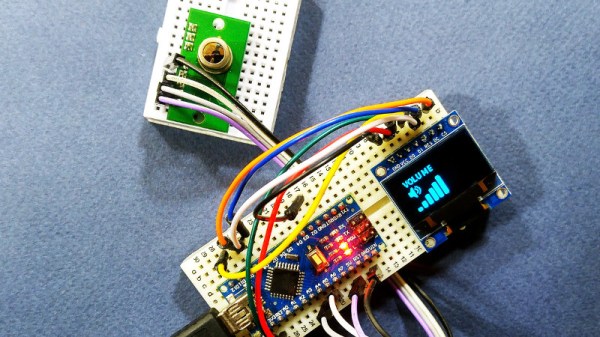

The project uses the TPA81 8-pixel thermopile array which detects the change in heat levels from 8 adjacent points. An Arduino reads these temperature points over I2C and then a simple thresholding function is used to detect the movement of the fingers. These movements are then used to do a number of things including turn the volume up or down as shown in the image alongside.

The project uses the TPA81 8-pixel thermopile array which detects the change in heat levels from 8 adjacent points. An Arduino reads these temperature points over I2C and then a simple thresholding function is used to detect the movement of the fingers. These movements are then used to do a number of things including turn the volume up or down as shown in the image alongside.