Getting people to space is extremely difficult, and while getting robots to space is still pretty challenging, it’s much easier. For that reason, robots and probes have been helping us explore the solar system for decades. Now, though, a robot assistant is on board the ISS to work with the astronauts, and rather than something impersonal like a robot arm, this one has a face, can navigate throughout the ship, and can respond to voice inputs.

The robot is known as CIMON, the Crew Interactive Mobile Companion. Built by Airbus, this interactive helper will fly with German astronaut Alexander Gerst to test the concept of robotic helpers such as this one. It is able to freely move about the cabin and can learn about the space it is in without being specifically programmed for it. It processes voice inputs similarly to a smart phone, but still processes requests on Earth via the IBM Watson AI. This means that it’s not exactly untethered, and future implementations of this technology might need to be more self-contained for missions outside of low Earth orbit.

While the designers have listened to the warnings of 2001 and not given it complete control of the space station, they also learned that it’s helpful to create an interactive robot that isn’t something as off-putting as a single creepy red-eye. This robot can display an interactive face on the screen, as well as use the same screen to show schematics, procedure steps, or anything else the astronauts need. If creepy design is more your style though, you can still have HAL watching you in your house.

Thanks to [Marian] for the tip!

Continue reading “I’m Sorry, Alexander, I’m Afraid I Can’t Do That”

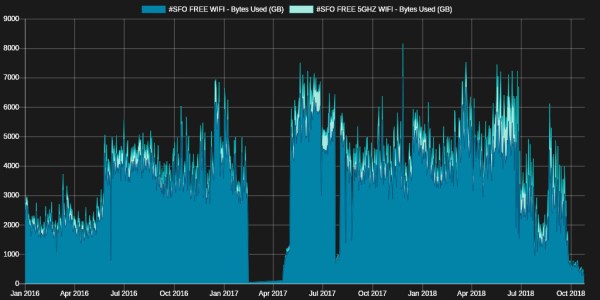

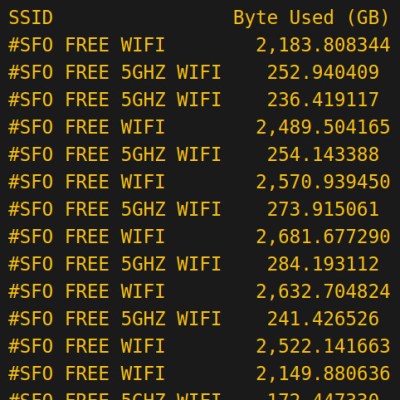

We’re not sure if this particular data mining hack falls under that description, but it’s good to know if you want information about what government is doing, you can get it and fast! From the first request to receiving the info was just 10 days.

We’re not sure if this particular data mining hack falls under that description, but it’s good to know if you want information about what government is doing, you can get it and fast! From the first request to receiving the info was just 10 days.