The biggest hurdle to great advances in wearable technology is the human body itself. For starters, there isn’t a single straight line on the thing. Add in all the flexing and sweating, and you have a pretty difficult platform for  innovation. Well, times are changing for wearables. While there is no stock answer, there are some answers in soup stock.

innovation. Well, times are changing for wearables. While there is no stock answer, there are some answers in soup stock.

A group of scientists at Stanford University’s Bao Lab have created a whisper thin co-polymer with great conductivity. That’s right, they put two different kinds of insulators together and created a conductor. The only trouble was that the resulting material was quite rigid. With the help of some fancy x-ray equipment, they discovered that adding a molecule found in standard industrial soup thickeners stops the crystallization process of the polymers, leaving them flexible and stretchy. Get this: the material conducts even better when stretched.

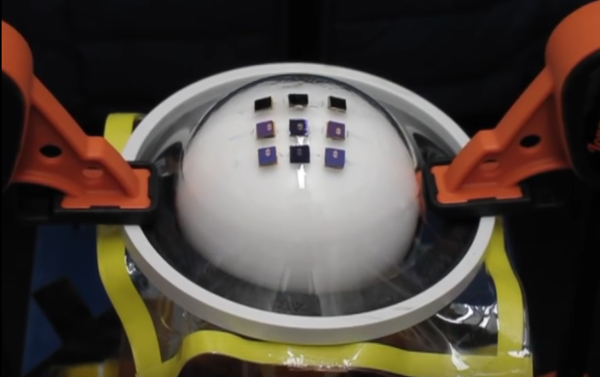

The scientists have used the material to make both simple, transparent electrodes as well as entire flexible transistor arrays with an inkjet printer. They hope to influence next generation wearable technology for everything from smart clothing to medical devices. Who knows, maybe they can team up with the University of Rochester and create a conducting co-polymer that can also shape-shift. Check out a brief demonstration after the break.