Picture this: you need to buy a simple tool like a glue gun. There’s usually not a whole lot going on in that particular piece of technology, so you base your decision on the power rating and whether it looks like it will last. And it does last, at least for a few years—just long enough to grow attached to it and get upset when it breaks. Sound familiar?

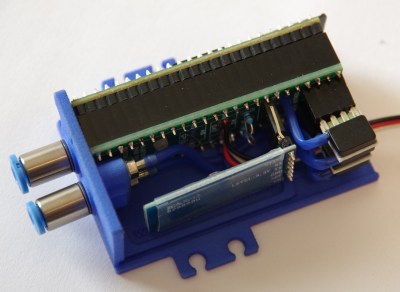

[pixelk] bought a glue gun a few years ago for its power rating and its claims of strength. Lo and behold, the trigger mechanism has proven to be weak around the screws. The part that pushes the glue stick into the hot end snapped in two.

[pixelk] bought a glue gun a few years ago for its power rating and its claims of strength. Lo and behold, the trigger mechanism has proven to be weak around the screws. The part that pushes the glue stick into the hot end snapped in two.

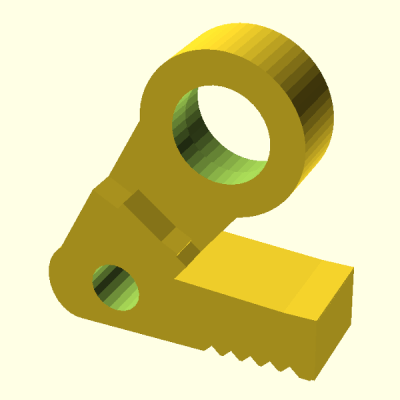

It didn’t take much to create a replacement. [pixelk] got most of the measurements with calipers and then got to work in OpenSCAD. After printing a few iterations, it fit well enough, but [pixelk] saw a chance to improve on the original design and added a few teeth where the part touches the glue stick. The new part has been going strong for three months.

We think this entry into our Repairs You Can Print contest is a perfect example of the everyday utility of 3D printers. Small reproducible plastic parts are all around us, just waiting to fail. The ability to not only replace them but to improve on them is one of the brightest sides of our increasingly disposable culture.

Still haven’t found a glue gun you can stick to? Try building your own.