How may radios do you own? Forget the AM/FM, GMRS/FRS radios you listen to or communicate with. We’re talking about the multiple radios and antennas in your phone, your TV, your car, your garage door opener, every computing device you own- you get the idea. It’s doubtful that you can accurately count them even in your own home. But what principles of the electromagnetic spectrum allow radio to work, and how do antenna design, modulation, and mixing affect it? [Michał Zalewski] aka [lcamtuf] aims to inform you with his excellent article Radios, how do they work?

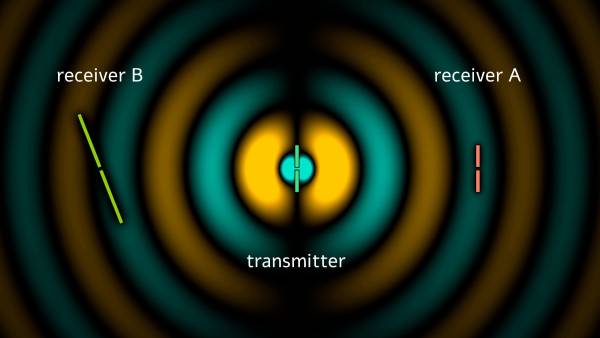

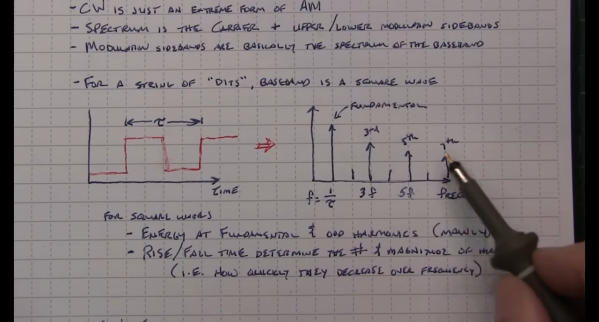

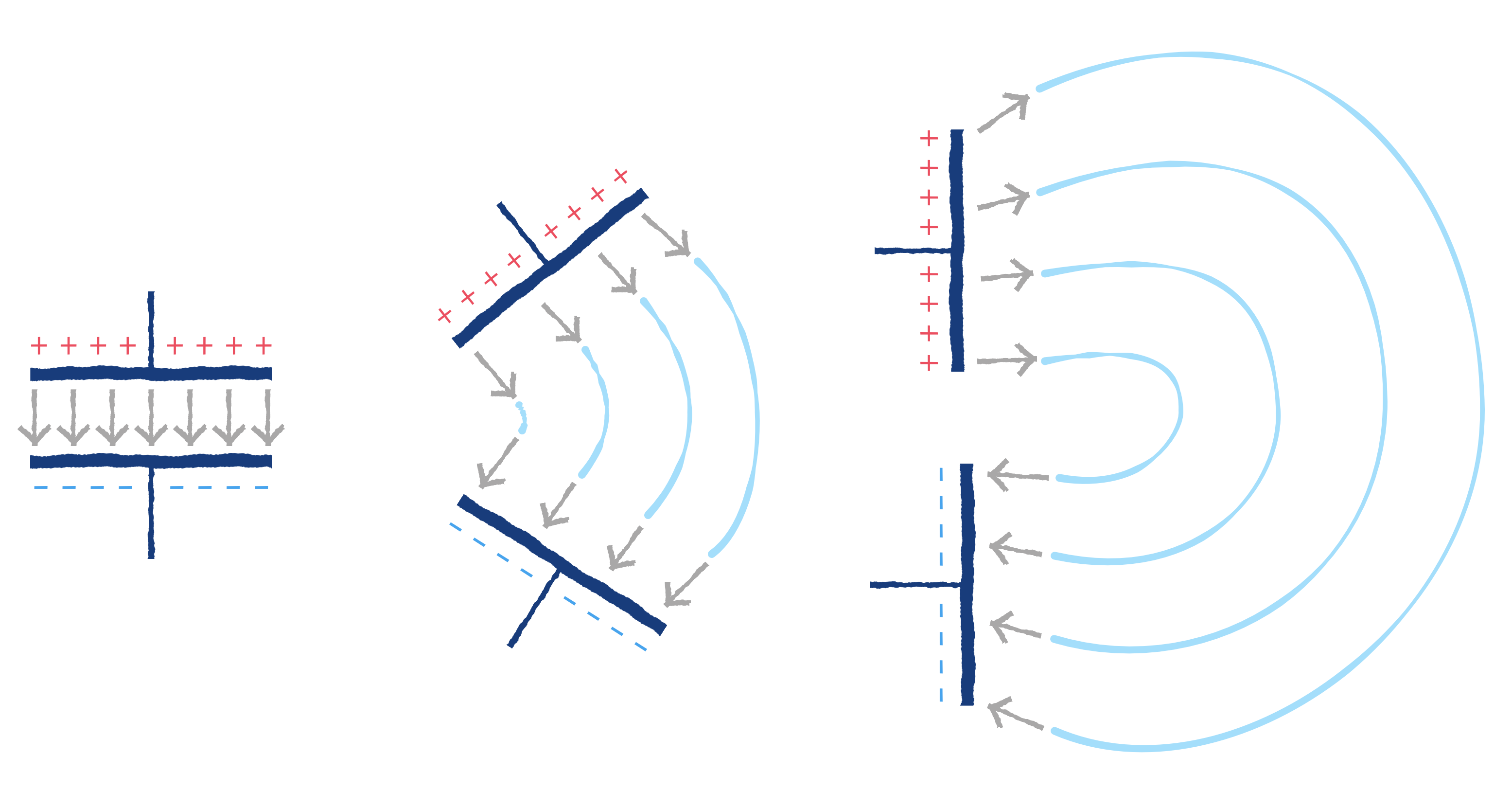

For those of you with a penchant for difficult maths, there’s some good old formulae published in the article that’ll help you understand the physics of radio. For the rest of us, there are a plethora of fantastic illustrations showing some of the less obvious principals, such as why a longer diploe is more directional than a shorter dipole.

The article opens with a thought experiment, explaining how two dipole antennas are like capacitors, but then also explains how they are different, and why a 1/4 wave dipole saves the day. Of course it doesn’t stop there. [lcamtuf]’s animations show the action of a sine wave on a 1/4 wave dipole, bringing a nearly imaginary concept right into the real world, helping us visualize one of the most basic concepts of radio.

Now that you’re got a basic understanding of how radios work, why not Listen to Jupiter with your own homebrew receiver?