As you may have noticed in our coverage, we’re big fans of OpenSCAD around these parts. The fact that several of the Hackaday writers organically found and started using the parametric CAD package on their own is not only a testament to our carefully cultivated hive mind but also to the type of people it appeals to. Hackers love it because it allows you to model physical objects as if you were writing software: models are expressed in code, and its plain text source files can be managed with tools like git and make. If you’re a real Pinball Wizard you could design objects and export them to STL without ever using a graphical interface.

But as you might expect, with such power comes a considerable learning curve. OpenSCAD devotee [Uri Shaked] recently wrote in to share with us his workflow for designing complex interacting mechanisms, which serves as an excellent primer to the world of parametric design. From animating your models to recreating the “vitamins” of your build, his post contains plenty of tips that can help both new and veteran OpenSCAD users alike.

But as you might expect, with such power comes a considerable learning curve. OpenSCAD devotee [Uri Shaked] recently wrote in to share with us his workflow for designing complex interacting mechanisms, which serves as an excellent primer to the world of parametric design. From animating your models to recreating the “vitamins” of your build, his post contains plenty of tips that can help both new and veteran OpenSCAD users alike.

Perhaps the biggest takeaway from his post is that you should be thinking of your projects as a whole, rather than as individual models. [Uri] recalls his early attempts at designing mechanisms: designing each component individually, printing it out, and only then finding out if it fits together with the other pieces. This method of trial and error is probably familiar to anyone who’s designed their own 3D printed parts — but it’s slow and wastes materials. The alternative, as he explains it, is to design all of the pieces at the same time and “assemble” them virtually. This will allow you to check clearances and fitment without dedicating the time and materials to test it in the real world.

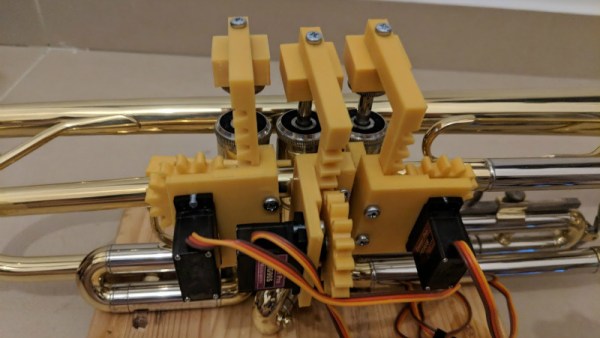

In fact, as [Uri] explains, you’re better off spending your time bringing real-world parts into OpenSCAD. By carefully measuring the hardware components you want to interact with (servos, gears, switches, etc), you can create facsimiles of them to use as a reference in your OpenSCAD project. As time goes on, you can build up your own library of drop-in reference models which will accelerate future designs.

He also spends a little time talking about something that doesn’t seem to be terribly well known even among the OpenSCAD converts: you don’t have to use the built-in editor if you don’t want to. Since OpenSCAD source code files are plain text, you can write them in whatever editor you like. The OpenSCAD model viewer even has an option specifically for this scenario, which will cause it to update the rendered preview as soon as it detects the source has been updated. For [Uri] this means he can create his designs in Visual Studio Code with a constantly updating preview in another window.

If you’re looking for examples of what the parametric capabilities of OpenSCAD can do for you, we’ve got no shortage of excellent examples. From creating customized computer cases to saving time by using mathematically derived components. Our very own [Elliot Williams] even has a write up about that most glorious of OpenSCAD commands: hull().