Prolific maker [Sean Hodgins] has taken the wraps off of his latest one-day build, and as usual, it takes the kind of spare parts most people reading Hackaday will have in their parts bins and turns it into something fun and useful. This time around, he takes a bunch of spare arcade-style buttons he had from a previous project and combines them with an Adafruit Trinket (SAMD21 flavor) to make a USB input device for his computer.

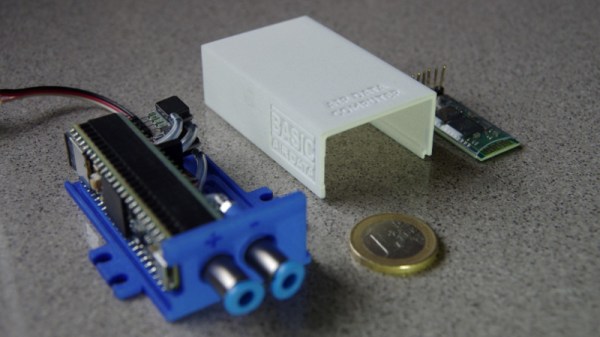

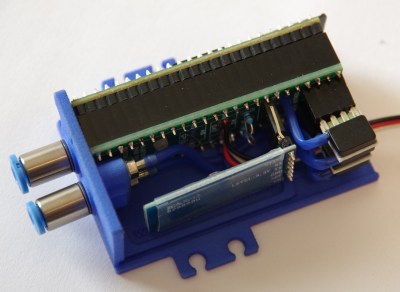

[Sean] uses 1/4 inch acrylic to make the case, though he does mention that it could just as easily be 3D printed. But using the acrylic is easy and gives a nice glossy look to the final hardware. With a saw and a drill press you can make some very professional cases out of acrylic, which goes to show that you don’t necessarily need to have a high end 3D printer to create great looking enclosures.

As explained in the video, the Adafruit Trinket is not strictly necessary for this build, it’s just what [Sean] had lying around. Any microcontroller that can present itself to the operating system as a USB Human Interface Device (HID) will work fine for a project like this.

Software wise, a modified Arduino demo program is used to equate the states of the digital pins to pre-defined key combinations to be sent to the computer. In this simple example the key combinations are hard-coded into the Trinket’s source code, but a future enhancement could be adding a method of setting up new key combinations with a configuration tool.

We’ve covered our fair share of non-traditional USB input devices, all operating on largely the same principle. As it turns out, hackers have quite a pension for making oddball input devices.