There are moments when current measurement is required on conductors that can’t be broken to insert a series resistor, nor encircled with a current transformer. These measurements require a completely non-invasive technique, and to satisfy that demand there are commercial magnetometer current probes. These probes are however not for the light of wallet, so [ensgoldmine] has created a much cheaper alternative.

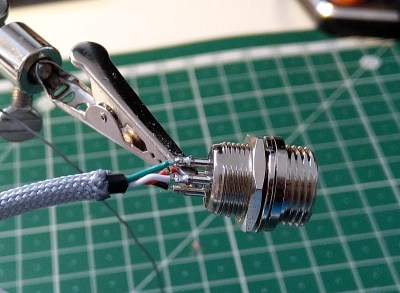

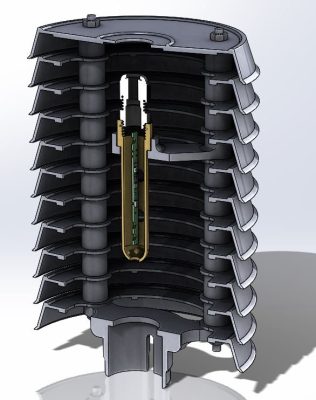

The Texas Instruments GRV425 flux gate magnetometer integrated circuit on its TI evaluation module provides the measuring element placed at the tip of a probe as close as possible to the conductor to be measured, with another GRV425 module at the head of the probe to measure ambient magnetic field for calibration purposes. An Arduino Due measures and processes the readings, chosen due to its higher-resolution ADC than the more ubiquitous Arduino Uno.

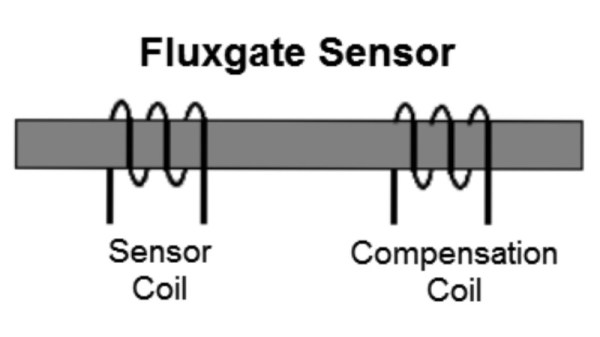

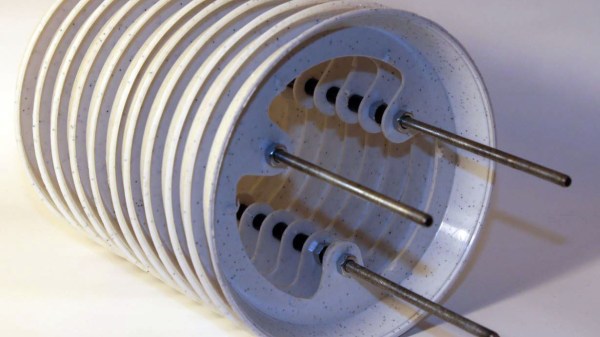

The write-up is interesting even if you have no need for a current probe, because of its introduction to these sensing elements. Because it’s a rare first for Hackaday, we’ve never taken a close look at them before other than as an aside when talking about a scientific instrument on Mars.