GPS jammers are easily available on the Internet. No, we’re not linking to them. Nevertheless, GPS jammers are frequently used by truck drivers and other people with a company car that don’t want their employer tracking their every movement. Do these devices work? Are they worth the $25 it costs to buy one? That’s what [phasenoise] wanted to find out.

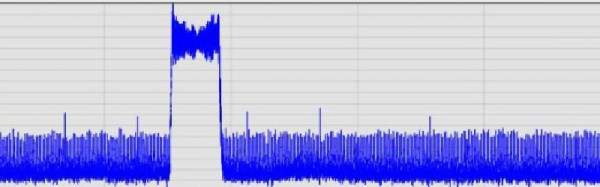

These tiny little self-contained boxes spew RF at around 1575.42 MHz, the same frequency used by GPS satellites in high Earth orbit. Those signals coming from GPS satellites are very, very weak, and it’s relatively easy to overpower them with noise. That’s pretty much the block diagram for these cheap GPS jammers — put some noise on the right frequency, and your phone or your boss’s GPS tracker simply won’t function. Note that this is a very low-tech attack; far more sophisticated GPS jamming and spoofing techniques can theoretically land a drone safely.

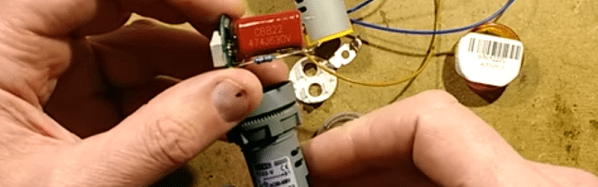

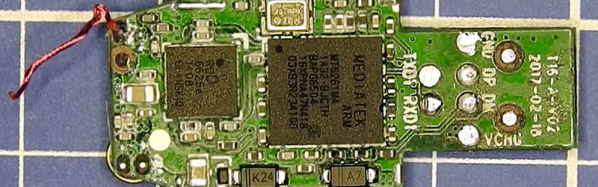

[phasenoise]’s teardown of the GPS jammer he found on unmentionable websites shows the device is incredibly simple. There are a few 555s in there creating low-frequency noise. This feeds a VCO with a range of between 1466-1590 MHz. The output of the VCO is then sent to a big ‘ol RF transistor for amplification and out through a quarter wave antenna. It may be RF wizardry, but this is a very simple circuit.

The output of this circuit was measured, and to the surprise of many, there were no spurious emissions or harmonics — this jammer will not disable your cellphone or your WiFi, only your GPS. The range of this device is estimated at 15-30 meters in the open, which is good enough if you’re a trucker. In the canyons of skyscrapers, this range could extend to hundreds of meters.

It should be said again that you should not buy or use a GPS jammer. Just don’t do it. If you need to build one, though, they’re pretty easy to design as [phasenoise]’s teardown demonstrates.