Elon Musk isn’t just the greatest human being — he’s also a great inventor. He’s invented the reusable rocket, the electric car, and so much more. While those are fantastic achievements, Elon’s greatest invention is probably the PowerWall. The idea of a PowerWall is simple and has been around for years: just get a bunch of batteries and build a giant UPS for your house. Elon brought it to the forefront, though, and DIYers around the world are building their own. Thanks, Elon.

Of course, while the idea of building your own PowerWall is simple, the devil is in the details. How are you going to buy all those batteries? How are you going to connect them together? How do you connect it to your fuse box? It’s a systems integration nightmare, made even more difficult by the fact that lithium cells can catch fire if you do something wrong. [jehugarcia] is building his own PowerWall, and he might have hit upon an interesting solution. He’s built a modular system to store and charge hundreds of 18650 cells. It looks great, and this might be the answer to anyone wanting to build their own PowerWall.

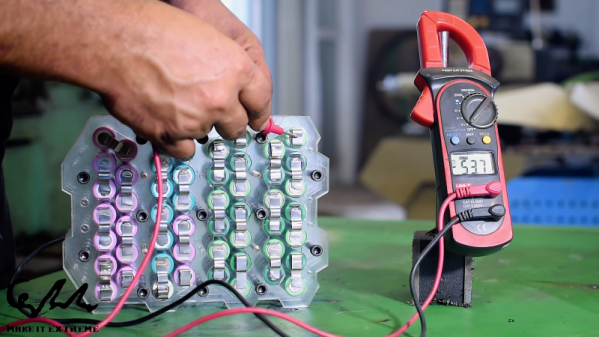

Aside from acquiring hundreds of 18650 cells, the biggest problem in building a PowerWall is simply connecting all the cells together. This can be done with 3D printed battery holders, solder, and bus bars, with a few people experimenting with spot welding wires directly onto the cells. This project might be a better solution: it uses standard plastic battery holders easily acquired from your favorite Chinese retailer and a PCB to turn cells into a battery.

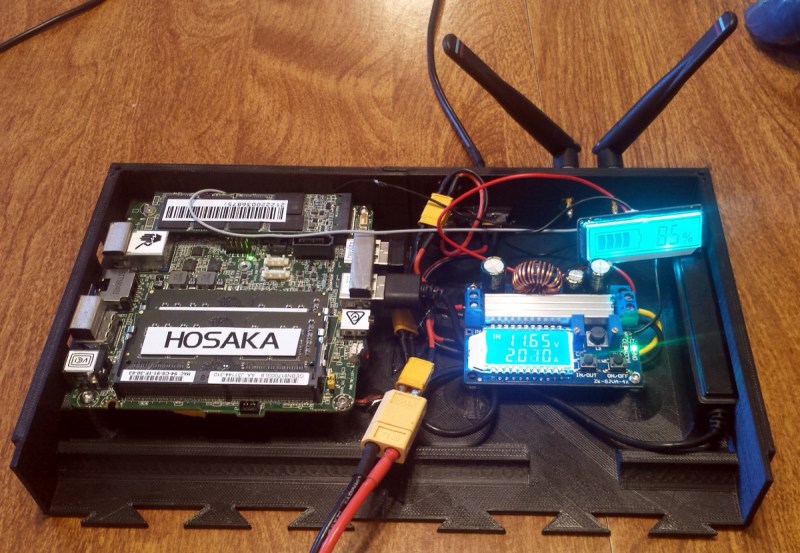

The design of this battery module consists of a PCB with sufficiently wide traces, an XT60 power connector, and a few headers for the balance connector of a charger. This is a seven cell setup, and in contrast to the hundreds of hours that go into making a PowerWall the old fashioned way, these modules can be assembled pretty quickly.

Testing of these modules revealed no explosions, and everything worked as intended. There was a problem, though: when drawing a high load, the terminals of these cheap battery connectors got up to 150°. That makes these modules unsuitable for high load applications like an e-bike, but it should be okay if you’re putting hundreds of these modules together to power your house. It might be a good idea to invest in some cooling, though.

Continue reading “The Quick-Build PowerWall”