You know those “What my friends think I do” vs “What I actually do” memes? Well there should be one for 3D printing that highlights what you think you’ll do before buying your first printer vs what you actually wind up printing once you get it!

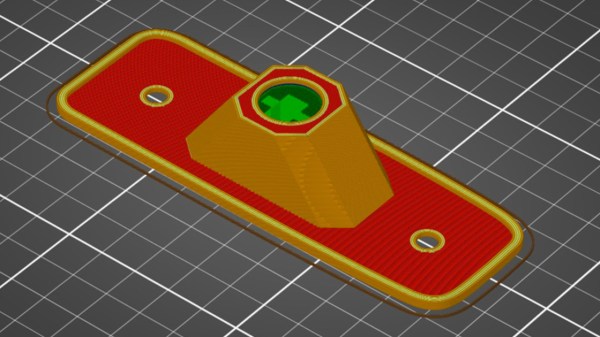

However, thanks to [Revolver3DPrints] you can fulfill your dream of printing a useful tool that looks like a commercial product, the Revolver two-speed screwdriver. The screwdriver isn’t motorized, but it has an interesting midsection that can be rotated to spin the bit, and you can select between a speed and torque mode.

The Revolver isn’t a solution looking for a problem. The designer noted a few issues with normal screwdrivers. They are hard to get into tight spaces, which was the biggest issue. The Revolver is compact, and since you turn its midsection, you don’t have to have clearance for your hand on the top. The gear ratios allow you to apply more torque without needing a long handle.

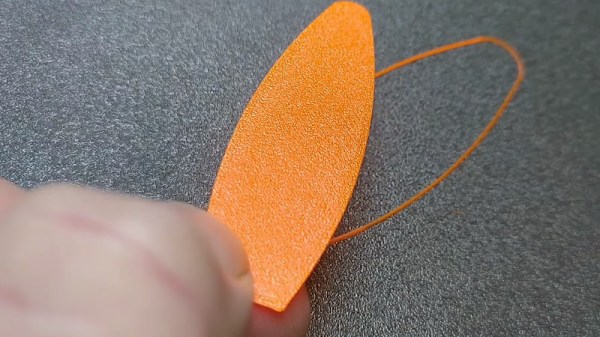

As you may have guessed, the internal arrangement is a planetary gear drive. You might consider if you want to print this using resin or FDM printing. You also need some screwdriver bits, some glue, and a few magnets to complete the project. If you prefer to make a motorized screwdriver, we’ve seen that done, too.