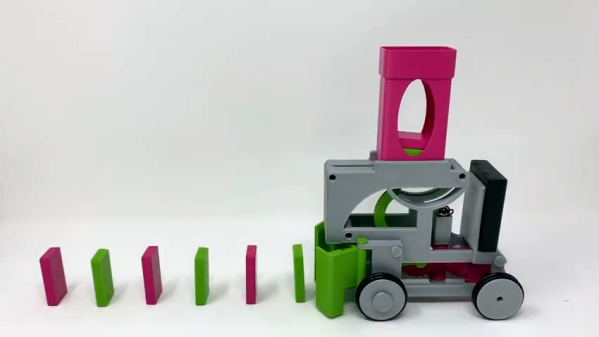

If you’ve been using Apple products since before they were cool, you might remember the Power Mac G5. This was a time before Apple was using Intel processors, so compatibility issues were high and Apple’s number of users was pretty low. They were still popular in some areas but didn’t have the wide appeal they have now. The high quality of the drilled aluminum design lived on into the Intel era and gained more popularity, but the case was still colloquially known as the “Cheese Grater”. Despite not originally being able to grate cheese though, this Power Mac actually does grate cheese.

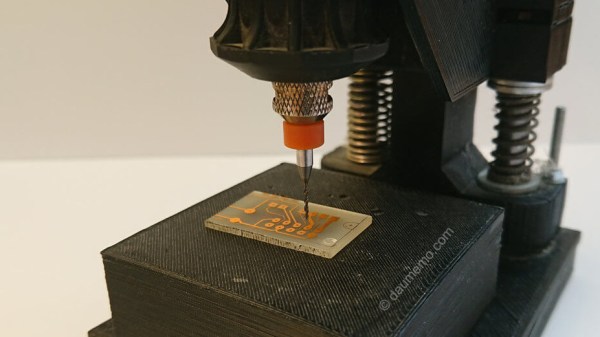

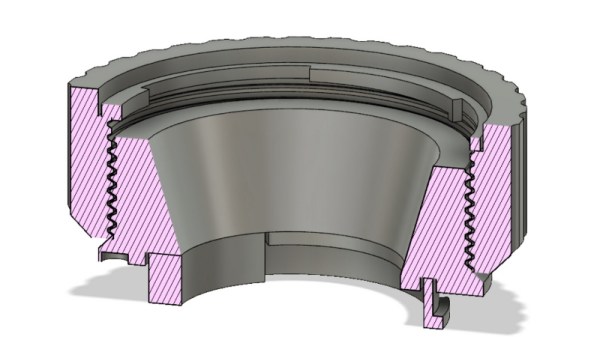

Ungrated cheese is placed in the CD drive slot where it passes through a series of 3D printed gears which grate the cheese into small chunks. The cheese grating drive is automatically started when it detects cheese via a Raspberry Pi. The Pi 4 also functions as a working desktop computer within the old G5 case, complete with custom-built I/O ports for HDMI that integrate with the case to make it look like original hardware.

Funnily enough, the Pi 4 has more computing power and memory than Apple’s flagship Mac at the time, and consumes about 100 times less power. It’s a functional build that elaborates on an in-joke in the hardware community, which we can all appreciate. Perhaps the next build should be something that uses the blue smoke for a productive purpose. Meanwhile, regular readers will remember that this isn’t the first Apple related cheese grating episode we’ve shown you.