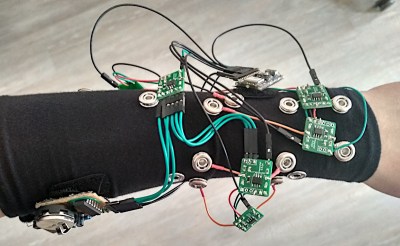

We don’t see many EMG (electromyography) projects, despite how cool the applications can be. This may be because of technical difficulties with seeing the tiny muscular electrical signals amongst the noise, it could be the difficulty of interpreting any signal you do find. Regardless, [hut] has been striving forwards with a stream of prototypes, culminating in the aptly named ‘Prototype 8’

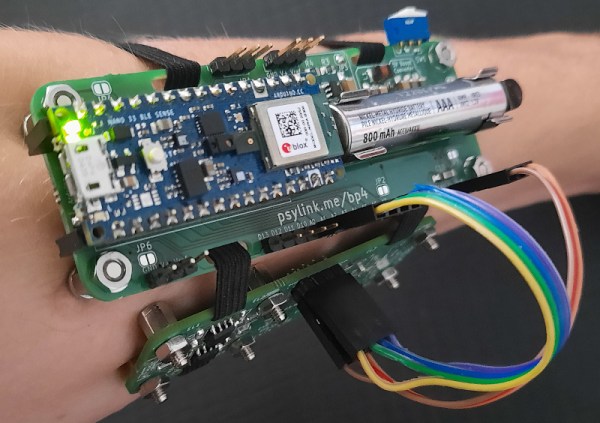

The current prototype uses a main power board hosting an Arduino Nano 33 BLE Sense, as well as a boost converter to pump up the AAA battery to provide 5 volts for the Arduino and a selection of connected EMG amplifier units. The EMG sensor is based around the INA128 instrumentation amplifier, in a pretty straightforward configuration. The EMG samples along with data from the IMU on the Nano 33 BLE Sense, are passed along to a connected PC via Bluetooth, running the PsyLink software stack. This is based on Python, using the BLE-GATT library for BT comms, PynPut handing the PC input devices (to emit keyboard and mouse events) and tensorflow for the machine learning side of things. The idea is to use machine learning from the EMG data to associate with a specific user interface event (such as a keypress) and with a little training, be able to play games on the PC with just hand/arm gestures. IMU data are used to augment this, but in this demo, that’s not totally clear.

All hardware and software can be found on the project codeberg page, which did make us double-take as to why GnuRadio was being used, but thinking about it, it’s really good for signal processing and visualization. What a good idea!

Obviously there are many other use cases for such a EMG controlled input device, but who doesn’t want to play Mario Kart, you know, for science?

Checkout the demo video (embedded below) and you can see for yourself, just be aware that this is streaming from peertube, so the video might be a little choppy depending on your local peers. Finally, if Mastodon is your cup of tea, here’s the link for that. Earlier projects have attempted to dip into EMG before, like this Bioamp board from Upside Down Labs. Also we dug out an earlier tutorial on the subject by our own [Bil Herd.]

Continue reading “PsyLink An Open Source Neural Interface For Non-Invasive EMG”

![The legendary Technics SL1200 direct-drive turntable, as used by countless DJs. Dydric [CC BY-SA 2.5)], via Wikimedia Commons.](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/640px-technics_sl-1200mk2-2.jpg?w=400)

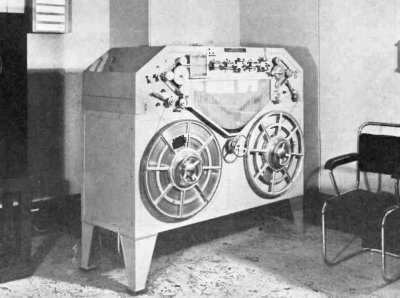

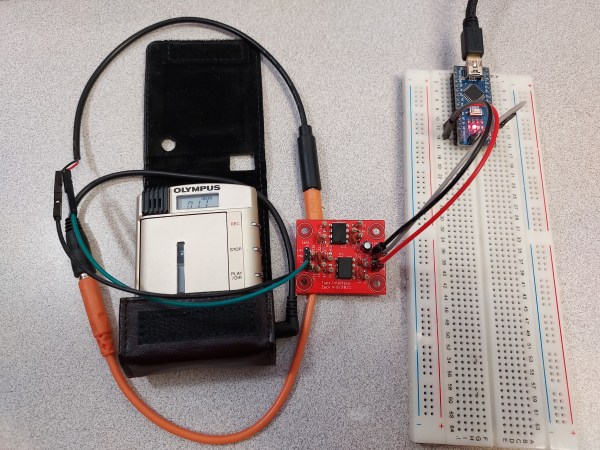

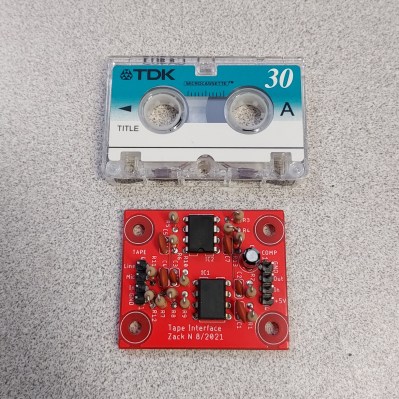

[Zack] designed the entire thing from the ground up: first he decided to use differential Manchester encoding, which provides immunity against common disturbances like speed variations (which cause wow and flutter). The data is encoded in the frequency range from 1 kHz to 2 kHz, which suits the bandwidth of the cassette player. Next, he designed the interface between the computer and the tape recorder; built from an op-amp and a comparator with a handful of discrete components, it filters the incoming signal and clips it to provide a clean digital signal to be read out directly by the computer.

[Zack] designed the entire thing from the ground up: first he decided to use differential Manchester encoding, which provides immunity against common disturbances like speed variations (which cause wow and flutter). The data is encoded in the frequency range from 1 kHz to 2 kHz, which suits the bandwidth of the cassette player. Next, he designed the interface between the computer and the tape recorder; built from an op-amp and a comparator with a handful of discrete components, it filters the incoming signal and clips it to provide a clean digital signal to be read out directly by the computer.