Chromecast devices have become popular in homes around the world in the last few years. They make it easy to cast audio or video from a smartphone or laptop, to a set of speakers or a display connected to the same network. [Akos] wanted to control the volume on these devices with a single, simple piece of equipment, rather than always reaching for a smartphone. Thus was built the CastVolumeKnob.

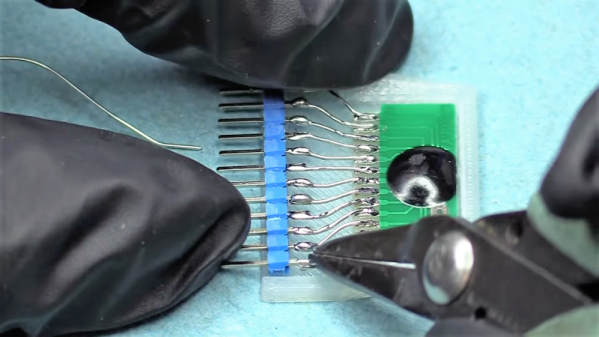

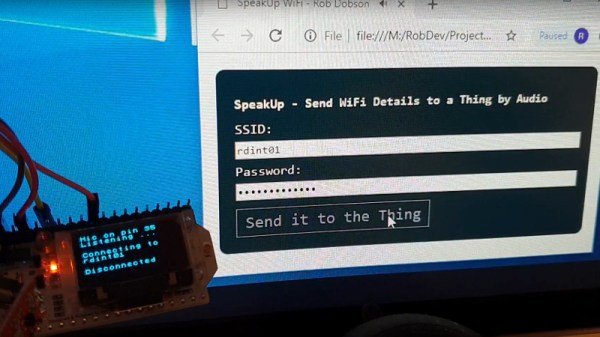

The project began by using Wireshark to capture data sent by the pychromecast library. Once [Akos] understood the messaging format, this was implemented in MicroPython on an ESP8266. A rotary encoder is used as a volume knob, and a Neopixel ring is used for visual feedback as to the device being controlled and the current volume level.

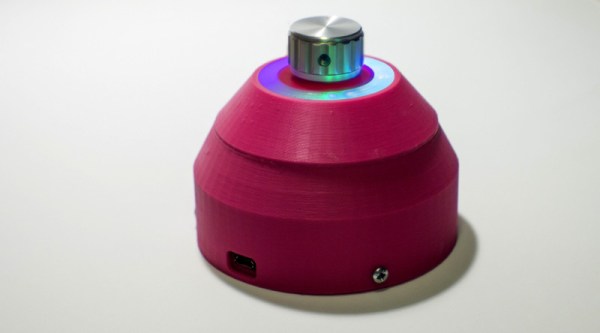

Further work was done to improve usability, with an ATtiny85 microcontroller being used to monitor the encoder for button presses before waking up the ESP8266, greatly reducing power consumption. The device is also rechargeable, thanks to an 18650 lithium polymer battery, and charger and boost converter boards. It’s all wrapped up in a sleek 3D printed case, with a translucent bezel for the LEDs and a swanky machined aluminium knob as the cherry on top.

It’s a homemade device that nonetheless would be stylish and unobtrusive in the living room environment. We imagine it proves very useful when important phone calls come in and it’s necessary to cut the stereo down to a more appropriate volume.

For another take, check out this USB volume knob with a nice weighty feel, courtesy of lead shot.